With Prohibition in effect from 1920-1933, a thriving trade in alcohol quickly arose in dozens of Maine and Canadian maritime communities.

Researcher and writer Daniel Sheldon Lee asserts in The Maine Lobster Boat, History of an Iconic Fishing Vessel: “Due to this proximity to Canada, during Prohibition, Maine would supply much of the nation’s liquor, just as they had supplied most of our nation’s lumber in the 19th century from the vast quantities of white pine cut in the logging camps along the Penobscot and other Maine rivers.”

Canadian Kellianne Dolan, in “Maine’s Prohibition: 82 Years in the Making,” (Maine Historical Society’s mainememory.net website), concurred, writing: “Bootleggers bringing liquor shipments into Maine ports or over the Canadian border were said to use the state as a conduit to distribute illegal booze all across the country.”

In Canada, Prohibition laws made it illegal to drink alcohol; but there was no prohibition on Canadian industries brewing whiskey, beer, and other alcoholic beverages.

The small islands St. Pierre and Micquelon in the Gulf of St. Lawrence are actually territories of France, residual land left over from the series of military conflicts incolonial times between France and England to control the future of North America. Ownership by France kept the two islands exempt from U.S. and Canadian laws governing Prohibition.

Ships carrying alcohol “imported” it to, and warehoused it on, these two islands. Canadian whiskey, French Champaigne, English gin, and Caribbean rum were shipped there then re-shipped to the “rum row” that set-up just beyond the 3-mile U.S. territorial limit off the northeastern coastline.

“Mother ships,” often old schooners and steamers, surplus World War I vessels, and ships of many other descriptions, all with liquor aboard, anchored in rum row, and were kept well-stocked with alcohol from St. Pierre’s warehouses, delivered frequently by rum runner boats.

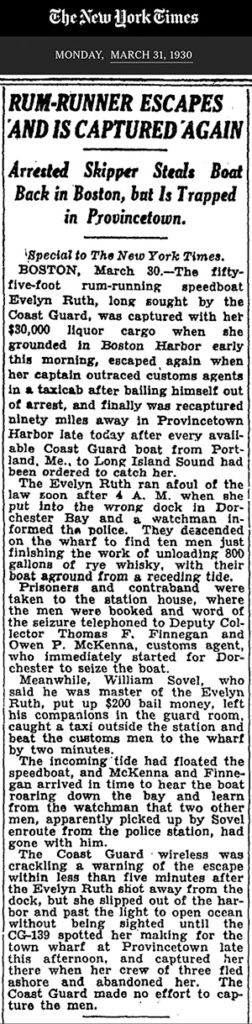

Mainers quickly capitalized on this new economic opportunity by taking their boats out to the mother ships on rum row to smuggle the illegal cargo to shore. Under the cover of nightfall, fishing and other kinds of “contact” boats would dart out from Maine’s shoreline to rendezvous with the mother ships and bring loads of booze ashore to isolated coves and remote docks where they would be quietly offloaded. Lee observed “To them, it was less a crime and more like an adventurous sport or a prank for profit.”

U.S. Customs agents were initially assigned to counter these contact boat deliveries to shore, but their ability to provide enforcement was severely limited by having been assigned only five boats for interdiction along the entire Maine coast. They were quickly overwhelmed. In 1923, responsibility for Prohibition enforcement along the U.S coastline was shifted to the U.S. Coast Guard which had far more vessels and crew to allocate.

The old freight and fishing schooners first used to transport and sell the bottles, tins, and kegs down to the Atlantic seaboard’s rum row were gradually replaced by bigger boats, made much faster to complete round trips to St. Pierre to replenish their alcoholic wares. The surplus World War I subchasers purchased by rum bosses were powered by three 220 horsepower engines that gave them a top speed of 18 knots. Shipbrokers commissioned Nova Scotia shipyards to build similar vessels for their clients.

The Kennebec Journal, on Dec. 12, 1923, carried an article titled “Rum Runners have the Speediest Boats.” The article reported that in New Jersey and Long Island, even a 30-mph rum runner was no longer considered fast, and area boatyards were building boats powered by two aircraft engines which provided speeds of 40 mph. These boats were said to be able to race to the newly established 12-mile limit and back in 40 minutes.

The typical “bottle fisherman” craft on rum row was 45-feet in length and capable of hauling 250 cases of liquor. “They look like lumbering old fish boats and travel like hydroplanes,” the newspaper reported.

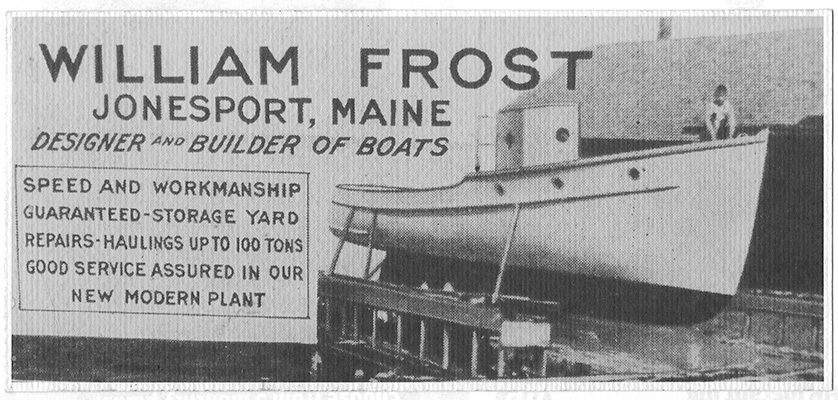

Downeast boatbuilder William Frost is generally credited with designing the semi-displacement hull that set the standard for rum runners. Jamie Lowell, William Frost’s great-grandson, interviewed in 1970 for the Northeast Archives of Folklore and Oral History at the University of Maine, noted that “Will Frost was the true originator of semi-displacement hull design and that was the origin of the Maine lobster boat as we know it. There were similar types of boats, but nothing like what he developed. Before him, they were taking displacement designs and lengthening them to be able to get speed. But Frost understood how the semi-displacement hull worked, from planing to running along to having a net in the water.”

Frost was born in 1874, raised at Digby Neck, Nova Scotia, and had learned the boatbuilding trade from his father and grandfather. He moved to Jonesport, then to Beals Island in 1912, recalled to Canada by the government for the World War I effort, and returned Downeast to a larger shop in Jonesport in 1928.=

His first lobster boats were designed with a rounded “torpedo” stern because that design worked well with low-power engines. In a following sea, a torpedo stern did not get pushed or tossed as a square-stern boat would. The to rpedo style sterns, though, were prone to weaken and spring leaks as they aged and fastenings let go.

rpedo style sterns, though, were prone to weaken and spring leaks as they aged and fastenings let go.

Frost developed the square sterned “semi-displacement” hull design that allowed a boat hull to lift out of the water and plane. He added spray rails at the bow to deflect spray away from the hull which increased boat speed by generating additional lift. He also placed rails just below the waterline on some of his later high-speed boats and underwater rails further aft to generate additional extra lift to help the boat onto plane.

Soon, Frost was building boats specifically for the illegal rum trade with vessels ranging from 30-feet to 80-feet long and traveling at speeds of 35 to 50 mph. Daniel Lee recounts that at one point, Frost was building rum runners at one end of his boatyard and the Coast Guard boats designed to catch them at the other.

Most of Frost’s rum runner boats were incognito, as well.

“They looked like fishing boats,” said Lowell. “They’d have a net out so they’d look like they were seining. It was all a façade to hide their activity. There were clues as to their true purpose, though. Small shelters left more deck space for cargo, and tiny porthole windows helped captain and crew dodge the revenuers’ bullets.”

Per Mike Crowe in “Rum on the Rocks,” in Fisherman’s Voice, March 1999, near-perfect rum runner vessels of 60 feet to 80 feet were powered with perhaps three World War I surplus aircraft engines like Sterling Vikings that could develop 565 horsepower, or the 12-cylinder Liberty, or the 6-cylinder Fiat powered boats that could not be caught by the Coast Guard. Painted gray, they were nearly invisible to the eye, and large 5-gallon drum silencers almost eliminated the sound of the engine.

In a 1976 UMaine Northeast Folklife Center interview, boatbuilder Harold Gower, who worked for Will Frost from the mid-1920s to the early 1930s, said of rum runners:

“You know, those boats were rigged with smoke screens. They’d run around and around the U.S. Navy ‘4 stacker’

destroyers that had been placed on loan to the Coast Guard, and by the time a destroyer got out of the smoke they’d be gone. Gone! They’d be up some creek or other, some cover, around some island, and land that booze and truck it off. They were owned by different parties, from Massachusetts and all along the coast. They were built light, inch and a quarter planking, just as light as could be. Of course, they were strong. They had to be to stand the weight and the speed.”

Another of the later rum runners was the Good Luck, a 65-foot Will Frost designed Jonesport-built boat powered by twin 300 horsepower 8-cylinder Sterling Viking engines of 565 horsepower each. Good Luck could reach speeds of 40 mph and made the run from Jonesport to the New Bedford, Mass. rum row in 22 hours.

The Prohibition era ended in 1933, but Frost’s semi-displacement hull design concept remains a fundamental component of boat design to this day.