Youth as Conservation Catalysts

Friday, July 21, 1882. Immediately after breakfast all members of the camp sailed out of the harbor and over to the seawall . . . About two hours were spent on shore, Townsend and Spelman with their guns and Clark with his hammer, confining their attention mostly to the rocks, while Rand and Lane wandered more wildly through the jungles and bogs . . . Their efforts were not altogether unrewarded by new species, but new species are not so very easy to get now . . . One important discovery was the location of skunk cabbage, which had been observed before on the islands, but never on Mount Desert itself. Two water plants still remain to be determined.

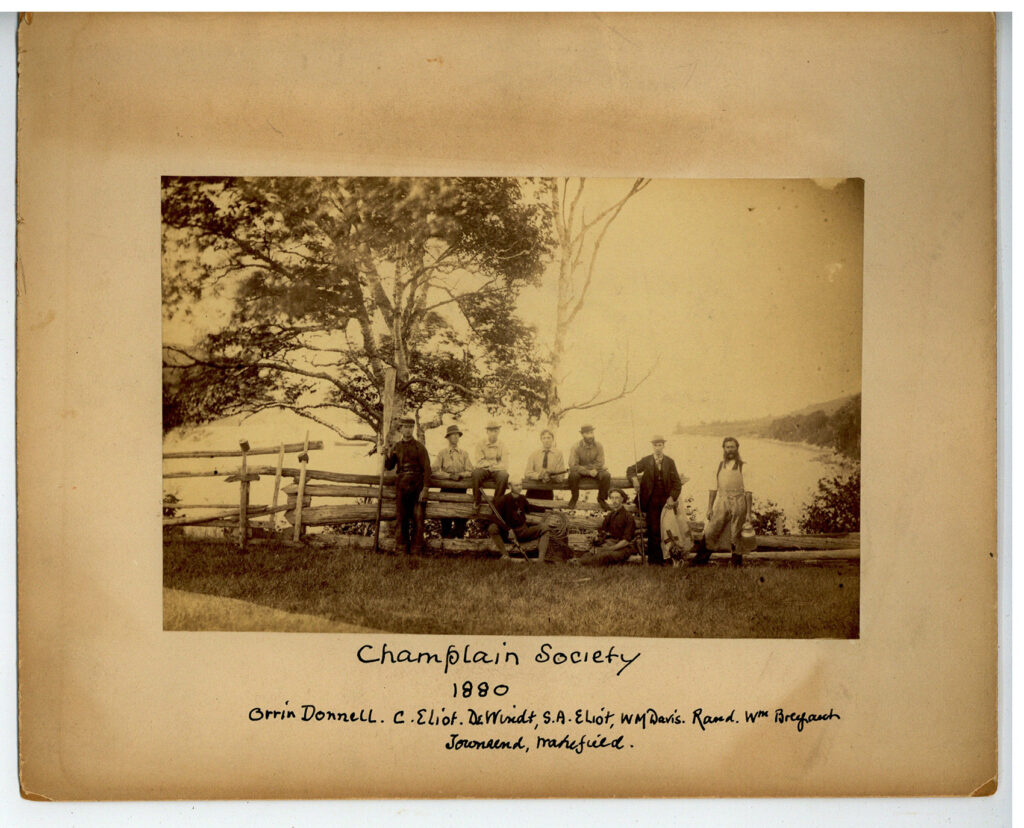

These words are from the journal of the Champlain Society, a group of Harvard students who conducted the first natural history surveys of Mount Desert Island, in the late 19th century.

Led by “Captain” Charles Eliot, son of Harvard president Charles William Eliot, they studied the island’s geology, weather, flora, and fauna. Their efforts are an important benchmark in the history of science in the region, a subject I have lately been researching and writing about.

The real significance of the Champlain Society, however, is its connection to conservation and stewardship. Its members were the first people to call for protection of the place now home to Acadia National Park, and their activities inspired the creation of the land trust model still in use today (through the career of Charles Eliot).

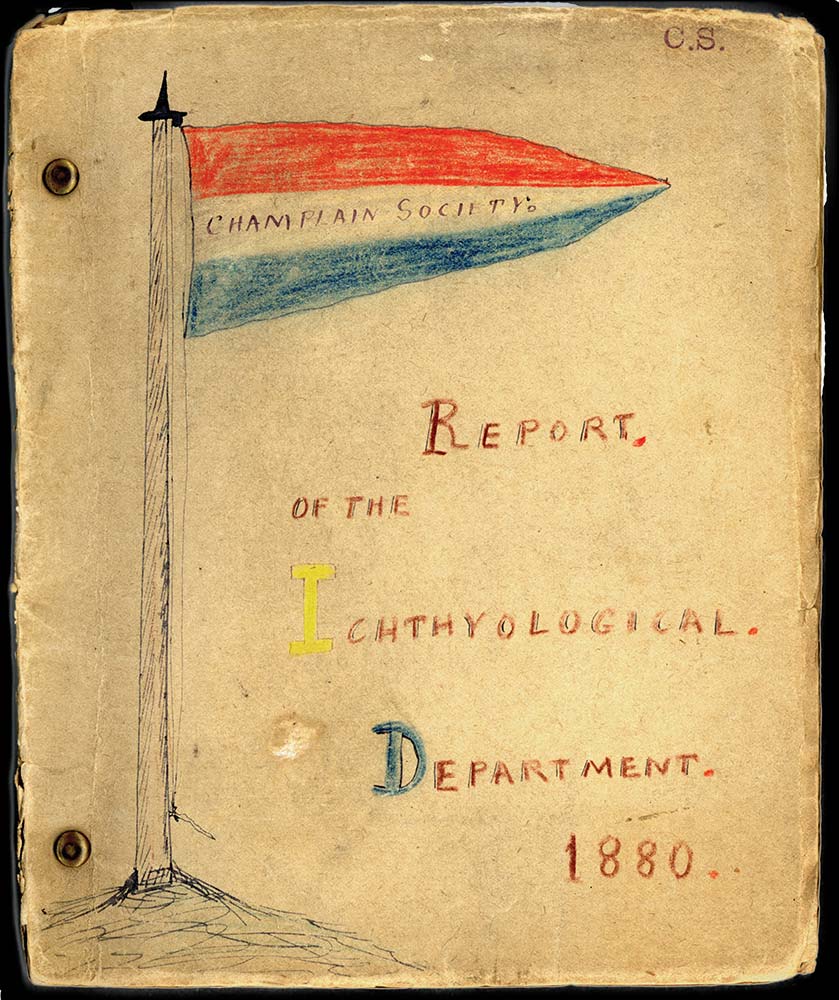

As part of my research, I’ve been transcribing the society’s camp journals and yacht logs, which detail their daily activities, walking and sailing around Mount Desert Island. Their words reveal a thoughtfulness and concern for the environment that seems well beyond their years. Here are William Dunbar and Edward Rand, writing on behalf of the group’s “Botanical Department” in 1880–81:

“Is it possible to protect the natural beauty of the island in any way? . . . A company of interested parties could buy at a small cost the parts of the Island less desirable for building purposes. To these they could add from time to time such of the more desirable lots as they could obtain control of either by purchase or by arrangement with the proprietor. This tract of land should then be placed in the charge of a forester and his assistants; the lakes and streams should be stocked with valuable fish; the increase of animals and birds encouraged; the growth of trees, shrubs, plants, ferns and mosses cared for. This park should be free to all on condition that no rules of the Association were violated . . . I hope, however, that we may have the pleasure before long of listening to a paper on this subject by one of its earnest advocates, ‘Captain’ Charles Eliot.”

And here, Eliot’s thoughts on the matter from 1883–84:

“The scenery of Mount Desert is so beautiful and remarkable that no pains should be spared to save it from injury—to the end that many generations may receive all possible benefit and enjoyment from the sight of it.”

The history of 19th-century conservation most often features older men of a certain type: Henry David Thoreau, George Perkins Marsh, John Muir, George Bird Grinnell, and, in the case of Acadia, George Dorr. The established narratives suggest that actions on behalf of special places come only with age, money, and, to some degree, power.

But Charles Eliot, Edward Rand, and other members of the Champlain Society were 18, 19, and 20 years old when they first began discussing the need to protect Mount Desert Island from ruthless flower-pickers, tree-cutters, and resort developers. Their concerns were not a casual aside, but can be found throughout their journals, which end in 1889, and then in the published writing of Charles Eliot, who went on to apprentice with Frederick Law Olmsted, eventually becoming a landscape architect. Until his death in 1897 at the age of 37, Charles Eliot called for conservation of Mount Desert Island, and “islands” of wild forest land around Boston. Much of his vision was realized in Maine, Massachusetts, and beyond.

Historically, then, Eliot can be placed among other students who throughout history have been at the forefront of intellectual and political revolutions, notes Philip Nyhus, an associate professor of environmental studies at Colby College. Nyhus is a member of the Conservation Catalysts Network (CCN), created by James Levitt, director of the Program on Conservation Innovation at Harvard Forest, and a fellow at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, along with colleagues at the Center for Natural Resources and Environmental Policy at the University of Montana. CCN’s mission is to explore the ideas of students, and the institutions they represent, as agents of land and biodiversity protection.

According to Nyhus—who helped CCN host a conference on students as conservation catalysts in March 2013—students approach new places, topics, and issues as learners, explorers, and listeners.

Young people have energy, time, and flexibility. They aren’t jaded or burned out. Optimists motivated by courageous ideas and contemporary trends, students believe they can make a difference, and so they do. When they become educators and disseminators of information, they don’t approach these roles as experts, and so are unlikely to be perceived as intimidating or threatening. Even if they aren’t totally conscious of it, their ignorance is a blessing, their naiveté a boon. Students don’t carry the burden of history, which can prevent the rest of us from thinking about things in new ways. They are innocent enough to ask, “Why not?”

The Champlain Society’s diaries are filled with the joy and pain of being on the brink of adulthood. The ages between 15 and 30 are when our most positive and vivid memories are made. Psychologists aren’t sure why. It could be because everything is new, and novelty begets memory. Or it could be due to the fact that young brains are physically robust and still growing. The most likely explanation, however, has to do with the formation of identity. A student is still figuring out who he wants to become, and, as he ages, he will hold on to those experiences that most contributed to his sense of self.

Such intense experiences include not just what happens and when, but where. The student members of the Champlain Society were in a place of stunning beauty and dramatic scenery at a crucial moment in their lives. They did not see themselves as tourists on a cursory visit. They were botanists, geologists, ichthyologists, meteorologists, entomologists, and ornithologists, staying in one place for weeks or months at a time, every summer, for nearly a decade. Imprinted with the sights, sounds, and smells of Mount Desert Island, they developed a “sense of place” that was key to their becoming catalysts for conservation.

More than a century later, a new generation is taking up the work of the Champlain Society. At every high school, college, and university are students with the energy and interest to learn about places near and far.

On Deer Isle, students are creating a new winter fishery for flounder. They are studying the fish, building traps, and applying for permits from the Department of Marine Resources.

On March 2, Maine college students joined hundreds of their peers in protesting the Keystone XL pipeline in front of the White House, and they continue to demand that their school administrations divest from fossil fuels. They don’t want their education to be on the backs of the very industries whose polluting activities threaten their future.

Since 2011, students from around the world have traveled to the Downeast region to participate in the Acadian Program in Regional Conservation and Stewardship, a short summer course focused on large, landscape-scale conservation.

All of this is making me feel old. There are many things I don’t remember from my days as a student, but I do remember—vividly, viscerally—the places where I worked. Now I know not to discount those experiences. They are a reservoir I draw from every day, and there is no end, no bottom to the well.