It’s an anniversary no one is celebrating. But it demands acknowledgement.

A group of waterfront business owners gathered for an Island Institute webinar on Jan. 16 to discuss the aftermath of the devastating coastal storms a year ago.

The stories that were shared elicited emotion, gratitude, and lessons.

Moderator Sam Belknap, director of the Institute’s Center for Marine Economy, was more than a curious observer; his family operates a wharf in Round Pond that purchases lobster and it was impacted by the storms.

The panel included Christina Fifield, who with her brother owns Fifield Lobster Company in Stonington, one of five buying stations in Maine’s largest lobster landing port.

“We’re on the smaller side,” she said, buying from about 40 boats.

“We thought we were prepared,” as they had raised the dock surface about 18 inches a year earlier after seeing a storm surge bring water within 6 inches of the decking in 2018.

“We were shocked and kind of disappointed” that building higher “didn’t really work out,” she confessed.

As the storm raged, they loaded heavy totes full of salt onto the decking to hold it in place. Despite that effort, “Our dock looked like a roller coaster,” Fifield said.

“We didn’t end up losing any of the actual planking,” but the business sustained substantial damage. Fishermen and neighbors arrived at the business, “trying to problem solve” ways to save the structures.

“After the initial shock of losing the wharf, we went into planning mode.”

—Amity Chipman

Fifield’s husband brought an excavator to the business, and a barge later was brought to the site to help with repairs. That barge was in demand, though, as it is the only one available in Stonington, she said, and some 25 docks needed work.

Two-ton mooring rocks now have been anchored under the dock, Fifield said, along with adding large steel I-beams and chains. One of the buildings has been raised 18 inches.

“We’re still rebuilding a year later and trying to figure it out,” she said.

She remembers people from the community “just driving in and jumping out of their vehicles, just trying to be helpful.”

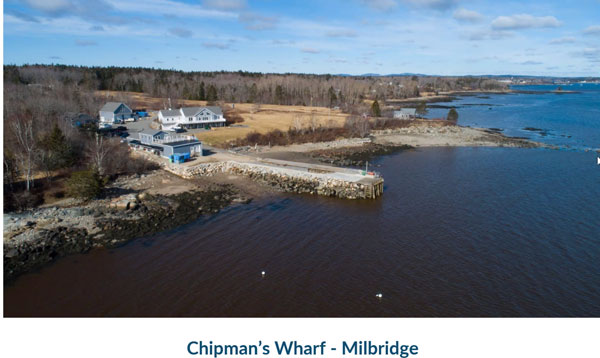

Amity Chipman, who, along with her husband and his brother and their family own and operate Chipman’s Wharf in Milbridge, saw the business’s wharf drift by her house.

“It was heartbreaking to see that,” she said.

“On Jan. 10, my sister-in-law called me and said, ‘It’s gone.’ I said, ‘What’s gone?’ She said, ‘The wharf is gone.’”

Some 800 lobster traps, stored on the wharf, washed away.

The wharf, which the two Chipman brothers and their father “built with their own hands,” served about 30 fishing boats. Chipman’s Wharf also is a tourism-oriented business, serving lobster and other food on the shore of Narraguagus Bay.

“That afternoon, all the fishermen showed up to help,” Chipman recalled, a theme among the panelists, crediting the larger community with assisting in stabilizing the properties.

She grew emotional in remembering the brief respite after the first storm, bracing for the second that came three days later.

The Chipmans were able to get dump trucks and an excavator on the property to begin repairs.

“Within days, the Island Institute was there for the business,” she said, offering information and support. “After the initial shock of losing the wharf, we went into planning mode.”

The family met with their insurance representatives and learned the damage wasn’t covered. FEMA—the Federal Emergency Management Agency—wasn’t able to help because the property is privately owned.

Then it was on to the federal Small Business Authority in search of a loan.

“It was an extremely frustrating process,” Chipman said, because staff were very slow to reply. The family finally learned the business could secure a loan at 4% interest, but only if their homes were put up as collateral.

Chipman’s Wharf finally secured a $271,000 state grant, half of the rebuilding cost, along with funds from Island Institute.

An engineer recommended that the new wharf be 42 inches higher, in a shorter, wider structure supported by cribwork. The surface will be concrete to make it heavier and less prone to lifting by storm surge. Plans call for extending the wharf farther into the bay.

Until the project is complete challenges remain.

“The boats are not able to access the end of the wharf for two hours either side of low tide,” Chipman said, and have to use the public wharf to unload.

“It’s been a challenging fishing season for our business,” she said. The rebuilding “has been a huge financial strain. We’re doing the work ourselves,” with the help of fishermen.

“It was very humbling to see the fishing community surround you. They’re family. They really support you when you’re in need,” she said. “We will persevere.”

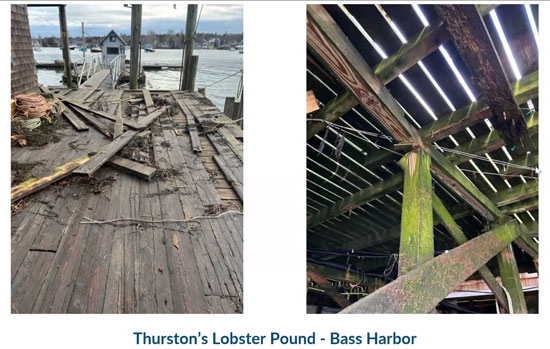

Derek Lapointe and his wife moved to Bass Harbor on Mount Desert Island 12 years ago to run the Thurston’s Lobster Pound business for her parents. She is the fifth generation of the family to operate there.

Despite building retaining walls before the storm, the surge disturbed about 100 pilings, Lapointe said. Utilities also were damaged, and “a 20-foot by 100-foot section of wharf” was damaged beyond repair.

The business started rebuilding immediately, he said, so those who fished in the winter months could still sell their catch.

Even with three kinds of insurance costing $32,000 annually—covering piers and docks, flooding, and storms—Thurston’s was unable to successfully file a claim. The business did land a state working waterfront grant to help with the rebuild, and permits are secured and a contractor lined up, Lapointe said.

Lissa Robinson, an engineer with GEI Consultants, listed the steps waterfront businesses should consider in rebuilding: conducting a site evaluation to assess overhead wires and sensitive environmental features; deciding whether rebuilding or a new build is appropriate; understanding the loads a pier will carry; and understanding what kinds of pilings to use.

She said designing the project typically costs 10% of the total budget. Design is recommended in gathering bids, Robinson added, making it easier to compare proposals.

In concluding the webinar, the Island Institute’s Sam Belknap noted that “Our strongest assets are our people.”