By Christa Thorpe

In the past few months, teachers all over the globe have seen their email inboxes flooded with educational resources for remote instruction. One teacher’s Twitter comment received nearly 2,000 sympathetic reactions: “Anyone else feeling a bit overwhelmed with all the resources shared—it is an abundance of awesome for sure but not quite sure how to navigate it.”

Monhegan Island teacher Mandy Metrano echoed that sentiment in an April webinar about teaching remotely following the closure of Maine classrooms due to COVID-19. Free online resources were suddenly pouring in from educational companies and other teachers.

“It was a lot to sift through. By no means could I explore them all,” Mentrano said.

Yvonne Thomas, education specialist at the Island Institute (publisher of The Working Waterfront), echoed that view. “The overall feeling is one of both appreciation and overwhelm,” she noted.

Teachers here are looking for Maine-based resources that students can use regardless of internet access. The Island Institute’s education team has been hearing for years about ways that coastal and island teachers utilize The Working Waterfront and other free local publications with their students. This seemed like the perfect opportunity to reach out and ask educators how and why they use the paper.

Here is some of what we learned:

Courtney Naliboff, a regular columnist for The Working Waterfront, teaches writing classes at North Haven Community School. “I use The Working Waterfront a lot,” Naliboff says. “Any time I’m teaching research-based or non-fiction narrative writing—it’s really important to have access to good anchor texts.”

For non-fiction narrative, Naliboff offers her own columns as examples, appreciating both the free access and ease of searching the archives online. For research-based writing examples, Naliboff likes that students see the types of sources they can access. Those interviewed in the stories are people the students know or can recognize—town managers, fishermen, road workers, DMR officials, ferry attendants.

Locally relevant anchor texts are more likely to engage students.

“Like my column about bridges on North Haven,” said Nabiloff. “Students have a lot of opinions on that issue, sometimes critiquing who I did and didn’t talk to, leading to discussion of how sources really change the tone, and that can help them think critically about what they read.”

Naliboff has also used examples from the paper for how to write a good “hook.” Christina Marsden Gillis’s essay about finding a shoe in the wall of an old house provided this one: “Its sole gouged with holes, the leather top cracked and ripped, the shoe, a woman’s, had been hidden in the west wall of an upstairs bedroom in our Gotts Island house.”

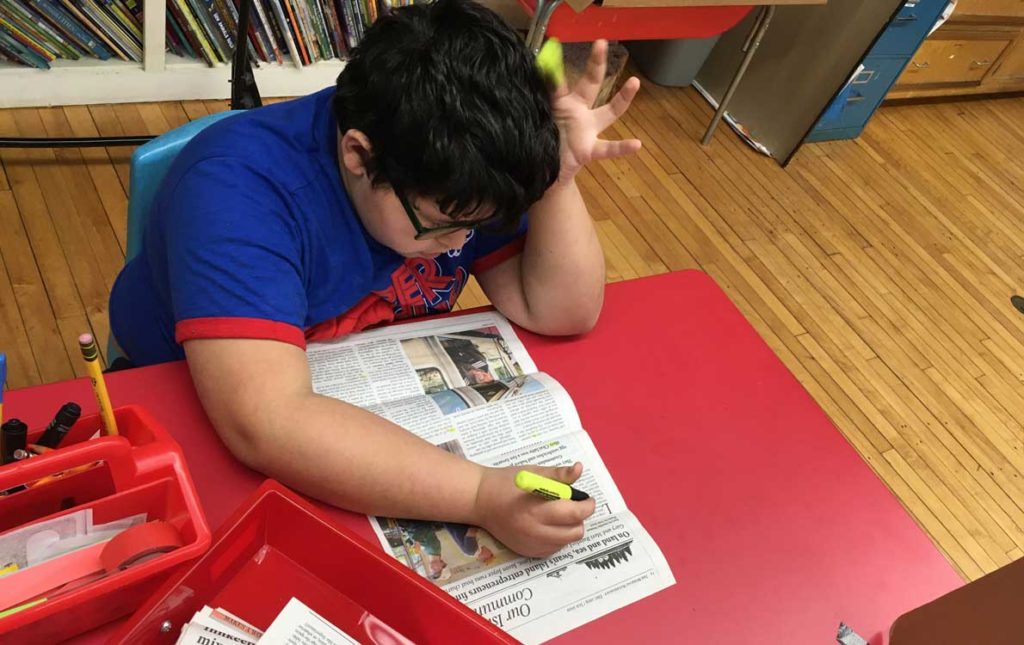

On the Cranberry Isles, Haley Estabrook uses print copies of The Working Waterfront in her K-4 literacy class. In the “Newspaper Detective” station, armed with highlighters, students scan the paper for certain patterns.

At Rockland’s Midcoast School of Technology, Sue Stewart teaches Technical Communications to prepare her students for the workforce, and the local Village Soup newspaper is a valuable tool. Students are assigned to look up a real job ad and work their way through the details to craft a cover letter and resumé as if they were applying for the job. It’s local and relevant to students—like The Working Waterfront, which Stewart says her students use often for research papers.

“I’ve got a lot of kids that lobster. Whenever rules and regulations come up, kids use the paper as a source for persuasive essays,” Stewart said. “The perspectives in the articles help reinforce students’ arguments or force them to re-evaluate their opinions.”

Hannah Noyes of Vinalhaven sums up the value of local papers well. A recent graduate of Connecticut College, Noyes was active on the editorial team of the college paper. She found local storytelling a helpful way to channel the often daunting and overwhelming effect of exposure to so many global perspectives and issues.

“Local publications are so important because they bring global issues closer to home. When students realize the topics they’re studying are relevant to their own communities, they feel better able to engage with the issues themselves,” she said. “It gives them a voice.”

Christa Thorpe works on education and broadband as a community development officer with the Island