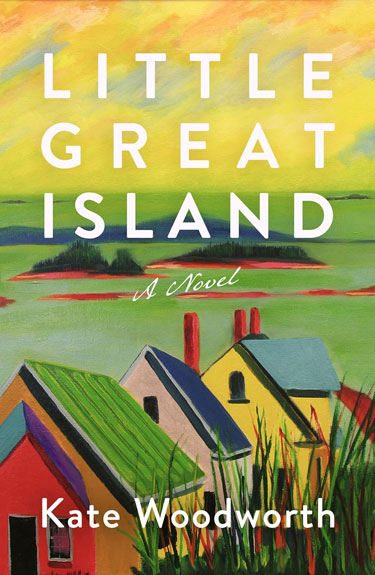

Little Great Island

By Kate Woodworth (Sibylline, May 2025)

Islands are tempting microcosms for storytelling. The fragile ecosystems, the upstairs/downstairs narrative potential of a summer and year round population relying on each other for survival, the weathered brow of the lobsterman—these are the low-hanging fruit of island-based novels.

Kate Woodworth has harvested some of that fruit for her upcoming novel, Little Great Island.

The titular island provides a backdrop for cult escapee and former year-round islander Mari and recently widowed summer resident Harry to collide, with pleasant but not unpredictable results.

The lobster are heading north, threatening the island’s way of life, and large tracts of land are considered for sale for McMansion subdivisions. Conflict makes the plot go ‘round, but it’s difficult to emotionally invest in the outcome because Little Great Island doesn’t feel like a fully envisioned community, the way inhabited islands must be, forced into self-sufficiency by their isolation.

The businesses and people we meet are painted in broad strokes and seen largely in relation to the seasonal population, and the nitty-gritty stuff of life is set aside in favor of the aforementioned weathered brows.

A central conflict of the novel is Mari’s desire to farm a few acres of Harry’s family’s land, something his lawyer sister dismisses as not right for the island.

The more interesting aspect of Little Great Island is the argument it makes for economic diversification. A central conflict of the novel is Mari’s desire to farm a few acres of Harry’s family’s land, something his lawyer sister dismisses as not right for the island. Woodworth makes it her job to put forward the argument for industry beyond lobstering and tourism, illustrated with interstitial scenes depicting the impacts of climate change on the plant and animal inhabitants of the island.

She’s correct, of course. For those of us who live on islands, the danger of a monoculture economy is hammered into us with Hurricane Island’s granite industry as a touchstone cautionary tale. The puzzling part is how controversial Woodworth seems to think this pivot is to island residents.

While change always brings naysayers, small-scale farming seems to have been generally well-received, at least on North Haven and Vinalhaven, where easier access to fresh vegetables makes everyone happy.

A more interesting diversification narrative might be the massive legal machine levied against new aquaculture operations in Maine, with NIMBY-ism masquerading as concern for the lobstering industry. But Woodworth keeps her eye on the microcosm, and the few acres of land are offered as a synecdoche for progress and change in a community that is more stubbornly resistant than feels realistic.

The story elements connected to Mari and her son’s escape from the cult build towards a climax that feels indebted to Richard Russo’s small-town Maine novel Empire Falls. It packs an emotional punch, but feels disconnected from the rest of the narrative.

Overall, Little Great Island is enjoyable, and for readers familiar with the Penboscot Bay islands, there are Easter eggs throughout that feel like inside jokes. Woodworth has some excellent points to make, but there remains so much more to say about island communities and why their survival matters.

Courtney Naliboff lives on North Haven and teaches at North Haven Community School.