The crossing of the Piscataqua River Bridge on I-95 or the aerial descent over Portland Harbor to the jetport signify arrival in Maine for most present-day visitors to Vacationland.

Before the development of automobiles, highway systems, and commercial airlines, coastal steamers were the primary mode of travel for visitors from major Northeast cities coming to Maine. For those seeking to enjoy the pristine woods and waters of inland Maine, disembarking steamer passengers were reliant on a network of transportation methods.

As the country rapidly industrialized in the mid- to late-19th century, a desire for fresh air and a return to simpler times grew within elite and middle-class communities seeking to escape overcrowded cities in the summer. Various published guidebooks raised awareness about the Maine woods and identified locations for potential visitors. Sporting camps and rustic retreats of the Rangeley Lakes region, Moosehead, and Sebago emerged as premier rural destinations touted for leisure activities like fishing, boating, hunting, and swimming.

Typical ships on the Boston-Portland route in the early 1900s featured well over 100 staterooms.

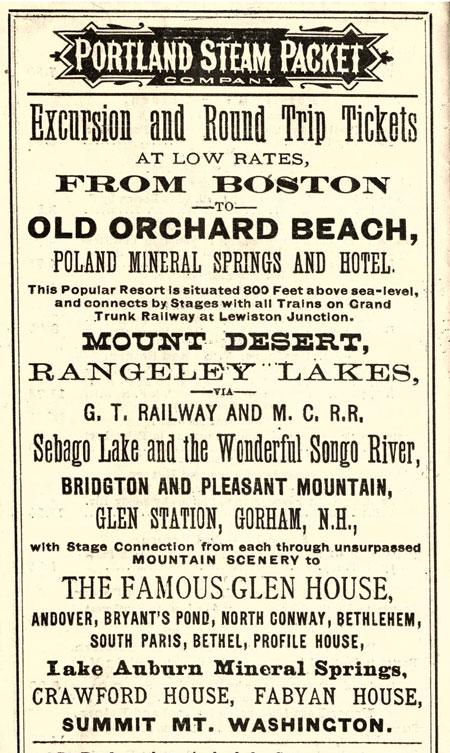

To entice tourists, railways and steamer lines printed brochures that touted Portland as the hub for inland destinations and explained the required network of travel methods. The Portland Steam Packet Company’s 1882 travel brochure, excerpted here, pushed combination travel tickets that started with their daily (except Sunday) overnight trips from Boston to Portland’s Franklin Wharf, the current site of the Maine State Pier.

The brochure neatly lists all these possible “excursion routes” and their respective fares. For $11 the trip to Middle Dam in the Rangeley Lakes region included: “Boston to Portland by Steamer; Portland to Bryant’s Pond by Grand Trunk Railway; Bryant’s Pond to Andover by Stage; Andover to Arm of Lake by Stage; Arm of Lake to Middle Dam by Steamer.”

Even after traveling over 24 hours to Maine by ocean steamer, and then to smaller inland communities by train and/or lake steamer, and then stagecoach, there was still another form of transportation needed to reach the most remote camps.

Occasionally, visitors would need to use a simple river ferry or a horse and cart team to reach their final destination and deliver their belongings.

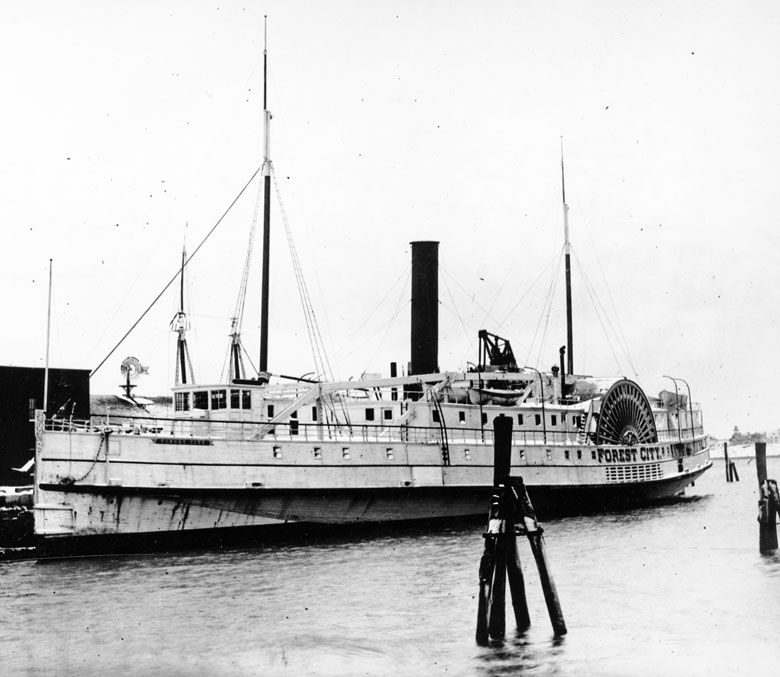

Pictured here is one of Portland Steam Packet Company’s coastal passenger steamers Forest City, operating for the 1882 season. The vessel was part of a fleet that also included Falmouth and John Brooks.

This steamship was built in 1854 and served a 40-year career on the Boston to Portland line. The growing demand for excursions to Maine throughout the late 19th century is evident in that typical ships on the Boston-Portland route in the early 1900s featured well over 100 staterooms, whereas Forest City only had 28.

The prevalence of the automobile later in the 20th century radically changed the travel landscape and provided greater amounts of control and freedom for tourists. It was not long before steamer and rail travel were a thing of the past.

Along with travel flexibility came a decline of the traditional sporting camps, resulting in the rise of individual camp ownership. Today, people can easily pack up their cars with their own equipment and amenities and arrive at camp in a matter of hours.

Kelly Page is curator of collections at Maine Maritime Museum. The museum’s newest exhibit, Upta Camp, further explores Maine camp culture and is on view through October 2025. Explore resources and plan your visit mainemaritimemuseum.org.