The new, cool kids on the sea-farming block get lots of attention—those folks growing mussels, scallops, oysters, and kelp. But there’s a well-established aquaculture sector turning out seafood along the Hancock and Washington county coasts.

Cooke Inc. has been operating in-the-water salmon farms in Maine for 20 years. The company was launched when brothers Glenn and Michael Cooke and their father Gifford Cooke established their first salmon farm at Kelly Cove, New Brunswick, in 1985. The company is now based in St. John, New Brunswick. It made forays into Maine by purchasing existing salmon pen operations. The first acquisition was Atlantic Salmon of Maine in 2004.

“There were about four players operating salmon farms in the early 2000s,” says Steve Hedlund, director of public affairs for Cooke’s Maine. Those firms, some of which were internationally based, were struggling financially, he said, and the Cooke family began purchasing those Maine businesses.

The acquisition included a salmon processing facility in Machiasport which still operates.

Today, the company operates in 14 countries and raises and harvests some 25 species, though Atlantic salmon tops the list of products. It runs 30 processing plants and operates several hundred vessels, employing more than 12,000 globally, Hedlund said.

In the U.S., Cooke operates in Virginia, Louisiana, Washington, and Alaska.

In Maine, Cooke employs 230 in Washington County, making it one of the region’s largest employers, with workers based in the processing plant as well as in locations along the Downeast coast that allow them to operate and maintain the 24 lease sites on which pens are located.

The Maine-raised salmon begin their life in three hatcheries: in Oquossoc (near Rangeley), Bingham, and East Machias. Once they reach a weight of 150 grams—about 5 ounces—they are placed in pens at the lease sites.

“We’re mimicking the life cycle of a wild Atlantic salmon,” Hedlund explained. The pens include a primary net suspended from a floating plastic frame. A second, “predator” net is hung on the outside of the pen to deter seals and diving birds from reaching the fish, and a bird net keeps eagles and ospreys from preying on the fish.

The pens are scattered across a region that extends from Cobscook Bay in the east, through Jonesport-Beals, to near Swan’s Island in the west. The fish spend about 18-24 months in the pens, reaching a weight of about 12 pounds, at which time they are ready to be sold.

Lease sites range from about 10 acres to about 45 acres, with most 20-35 acres.

“Then the farm site is fallowed for months,” he said. The two-dozen lease sites allow for rotating production. Though the pens might seem to be devoid of much human attention, Hedlund said “There’s a lot of maintenance required.”

In the early stages of the salmon’s life, workers feed the fish by hand at the pens, but later, it’s automated, with workers using remote technology to provide feed.

“Each farm has a feed barge,” he said.

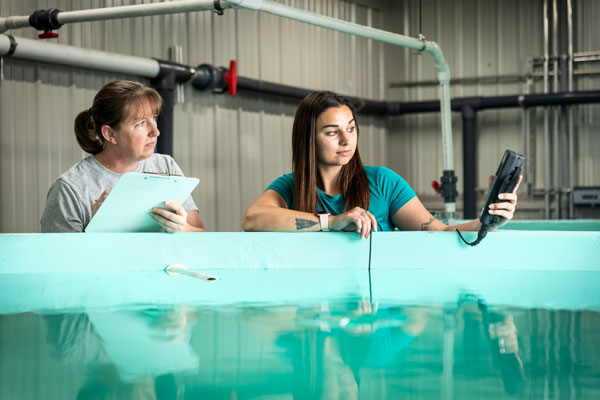

Underwater cameras monitor the feeding, and air is used to move it around and suspend it in the water for a time, thereby limiting what ends up on the bottom.

The feed is a blend of fish meal, fish oil, a vegetable protein (like soy), and vitamins and minerals. One ingredient, astaxanthin, derived from shrimp, krill, and other crustaceans, gives the salmon its pink color.

“It’s dry, pelletized,” he said of the feed. Critics say the uneaten feed that falls to the bottom can be a pollutant, but Hedlund counters that, noting “We’re constantly monitoring the environment,” including the sea floor, to ensure that very little makes it to the bottom.

The fish are vaccinated before they’re transferred to farm sites to reduce bacterial diseases.

State law limits stocking density of salmon at 30 kilograms per cubic meter; Cooke’s density is lower than the required density, he said.

In the 1980s, when pen-farming emerged Downeast, there was resistance, for a variety of reasons—impacts to views, concerns about loss of access for lobstering and other fishing, and concerns about environmental impacts, including the escape of farmed fish.

Hedlund and others in the industry acknowledge that early errors were costly to community perception, and that being responsive to concerns is key to success.

“Social license is everything,” Hedlund said, referring to a buy-in from communities. “It’s so important. We hold a lease. It’s a privilege.”

The company is regulated by the state’s Environmental Protection and Marine Resources departments, as well as the federal Army Corps of Engineers. Escapes must be reported, and the company submits to third-party audits.

Hedlund noted that all of Cooke’s Maine pens survived the January storms.

“They’re pretty weather-resistant,” he said.

Still, “There are challenges to raising animals,” he said, with sea lice and diseases that appear from time to time. “Like any industry, you’re constantly improving and learning,” he said, and the company invests significantly in research and development.

He disputes the idea that lobstermen see fish farms as interlopers.

“Some lobstermen and women work for us in their offseason,” he said. “We’re always helping each other out there,” towing stranded boats and assisting it other ways.

“We’ve been coexisting in Downeast Maine for 42 years now. They set gear next to our [pens].”

Cooke’s salmon is sold under the True North brand in local grocery stores, and in stores across the country. Most of the salmon processed in Machiasport is sold at supermarkets and restaurants in New England and the Northeast, Hedlund noted.

The “made in Maine” nature of the product adds value. Monterey Aquarium rates farmed salmon as a “good alternative”

“It resonates with consumers,” he said, as the marketing touts the pristine waters of the Gulf of Maine as the source.

Atlantic salmon provides a high source of omega-3 fatty acids, which provide a number of health benefits.

“It’s such a consistent source of protein for people worldwide now,” especially when it is farm raised. That steady supply “opened up the salmon market,” he said. Salmon is the second most consumed seafood in the U.S. behind shrimp.

In addition, “Fish is such an efficient converter of protein,” with 1.2-1.5 grams of protein feed resulting in 1 gram of fish flesh.

Workforce, as with many sectors, remains a challenge, but Washington County Community College now offers an aquaculture certificate program.

“We’re always advertising vacancies,” including for deck hands and fish-processing technicians.

About 35 people working for Cooke in Maine were with the companies Cooke acquired, meaning they have been in their jobs for 20-plus years.

Gov. Janet Mills congratulated Cooke on its 20 years in Maine:

“Maine’s iconic seafood industry is a key part of our state’s heritage and a cornerstone of our economy. Cooke has been a leader in seafood production in Maine, employing hundreds of people in high-quality, good-paying jobs. I congratulate Cooke as it marks 20 years in Maine and thank this family-owned business for its extraordinary contributions to the Maine economy.”

In a press release, Cooke quoted Chris Gardner, executive director of the Eastport Port Authority and chairman of the Washington County Commission: “Cooke, and salmon aquaculture in general, are woven into the fabric of Washington County’s economy. Not only does the company provide direct employment to people in Eastport and throughout Washington County, but it also supports numerous other businesses that provide goods and services year-round, helping sustain the region’s ocean-based economy.”

Sebastian Belle, executive director of the Maine Aquaculture Association (and a member of Island Institute’s board of trustees), also praised the company’s contributions.

“The company is family-owned, regionally based, and competitive with well-established sales and marketing channels, and that it has operations here in Maine gives the state a seat at the table in the global salmon arena.”