New York City just didn’t agree with Dave Morrison. The music scene was a clutter of competition and costs he hadn’t encountered playing nightclub circuits in New England. Living arrangements were expensive. Waiting tables at the Hard Rock Café was less than satisfying. Transportation was awkward, especially lugging around guitars and other equipment associated with rock and roll performances and recording. The music business was losing its charm.

So he and his wife chucked the big city and moved to Maine.

Why Maine?

“Because it was beautiful,” he said in a recent conversation at his house in Camden. He had played many gigs north of Boston at the height of his rock and roll days in the 1980s, and he and Susan had visited friends in Maine and liked it. So with no jobs, no prospects, and next to no money, they came to the coast and have never looked back.

“It felt like home right away,” he said. “Familiar. Comfortable.”

That was in 2005. Morrison soon found work as facility manager for the venerable Camden Opera House, a position he still holds. It seems like an appropriate niche for a guy who has dedicated most of his 57 years to entertainment and the arts—notably, in his post-rock-star years, poetry.

Psalms

His newly published book, Psalms, is his 12th collection of poems since 2006, not to mention a music and spoken-word album, Poetry Rocks (Mishara Music, 2015). His poems have appeared in small magazines and anthologies, in former Maine Poet Laureate Wesley McNair’s “Take Heart” column, and on Garrison Keillor’s “Writer’s Almanac” radio show. He’s appeared on WERU radio’s Writers Forum, hosted the “Have Poems, Will Travel” show on WRFR-FM in Rockland, and given performances of his poetry widely in Maine, including at the opera house.

LOVE LABOR LOST

Before his life in poetry, though, he was a small-venue rock star in Massachusetts, where he grew up in the town of Reading. He played guitar from his teenage years and became a rock and roll regular in the down and dirty Boston-area clubs and bars. Among his most successful bands were True Blue and The Trademarks, who played throughout New England, including excursions to Portland’s lively 1980s music scene, as well as to clubs and ski resorts in New Hampshire and Vermont.

In the 1990s he tackled New York under the band name Juke Savages. The competition was keen, and piecing together practice time and musicians (some of whom demanded regular salary for on-call work, which Morrison had never encountered in Massachusetts) in between trying to scrape together an income became a wearying process instead of the labor of love it had been in his 1970s and ’80s youth. He found his attention, from one day to the next, drawn less and less to his guitar and more and more to writing. Time to make a change.

In the late ’90s he enrolled in creative writing classes in New York’s New School, thinking to channel his creative energies into a more private, less frantic daily routine. But music was not easy to let go of, he said. It was the core identity of the first half of his adult life.

“I’m good at it. It seemed like what I was built to do,” he said. And so “the illusion for years was that ‘home’ is playing music.”

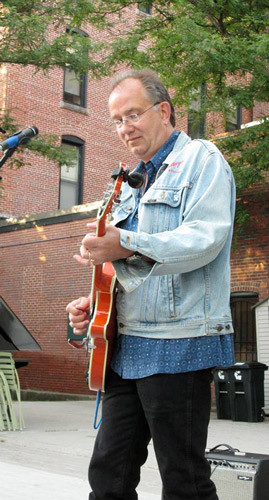

Dave Morrison playing in Portland.

On the other hand, in songwriting, “the lyrics always came first,” he said. “Melodies develop out of the words.” So while the shift in self-definition from musician to poet was not instantaneous, the transitions “from music to writing memoirs, to novels, to short stories, to poetry” were more than natural. After writing two novels, Hideaway and Camaro, he concluded that his real literary calling is poetry. “It suits the way I’m wired,” he said.

Finding a home in writing poetry coincided with the move to Camden, and the poetry he’s written since seems to reflect what he calls a “homecoming.” Morrison’s books are full of sights and sounds from the Maine coast—little narratives of people and scenes seen, brilliant natural images (“Haiku Composed While Raking”: “The bill just came due/for all the lovely shade we/enjoyed all summer”)—along with relentless, straightforward questions about what it all means, what we’re all doing here, and how we can make good lives—much like the one he’s made in Camden, it seems. Writing itself is “a way of finding your way home,” he says.

CANCER POEMS

Most of Morrison’s earlier collections gathered recent work, while a couple are thematic to times and places. Clubland (2007), one of his best overall books, gathers versified reflections, stories, and character sketches from his life in rock and roll, and offers palpable energy from the poetry-music nexus. His 2015 book Cancer Poems discloses the inner workings of a yearlong battle with throat cancer in which his acute capacity for metaphor proved a potent ally:

I just passed a mirror and I saw

Satan as a young man,

just after his girlfriend

broke up with him; scorched, sullen.

After his ordeal, Morrison went to ground artistically, and had somehow to come to internal terms with “the shrapnel I was carrying around.” His creative outlet came in the form of a project he’d contemplated for years: building a guitar named Wonderboy. The hands-on tactility of the work helped him recharge his spiritual (not to mention verbal) energies, and his poetic voice re-emerged and culminated this year in Psalms.

“The feeling of homecoming seems a little more profound to me this time,” he said of the publication of the new book. And while he acknowledged but played down the impact of the cancer episode, it seems clear from the 100 poems in Psalms that he feels changed, poetically and personally. Poem No. 35 may be a clue to the tenor of the change; in its entirety:

Finally I am

as ordinary as

a crow by the side

of the road; wise,

hungry, detached.

The brevity and concision of this poem are not new to Morrison’s style, but they’re the most prominent formal characteristics of Psalms. The longest poem in the book has only 28 lines, and the vast majority have far fewer.

A hallmark of his poetry is its accessibility, a term the creative writing industry employs to characterize poems whose literal meanings are easy to grasp. But contrary to certain academic belief systems, a poem’s depth can’t be reliably measured by the incomprehensibility of its surface. Morrison’s aim is not to plumb profound abstract philosophy, but to entertain people in language with musical roots.

And the hope, he said, “is that it’s useful … more than just decorative. The hope is that it triggers some little thing in your head, and expands.”

The poems in Psalms are, like the biblical psalms, songs of joy and gratitude, “small exclamations.” And from the plain-spoken lines and crystal clear imagery, a sense of spirituality arises that reminds a reader of the purest moments in the Bible and other spiritual traditions, notably Hafiz and Rumi, Islamic poets of the middle ages. Indeed, the opening lines of the book could be a contemporary version of one of Rumi’s wry addresses to the Beloved, or God:

How I have resisted

you: love, but not

love of my life;

mate but not

soul-mate;

choice, but not

first choice.

Knowing and determined

you have clung to

my side, waiting for the

madness to pass.

Although it isn’t necessarily God who’s being addressed here, the spiritual underpinnings of these poems don’t rule out that sensibility expanding in your head. This is a poet whose inner awareness and struggle to make sense of the world come through in energies beyond the wavelength of your rational understanding. Just the way music does.

Poetry is a component of everyday life, for Dave Morrison. He stays alert for its sudden appearances every humdrum hour with the pure, innate joy of “a dog sticking its head out the car window,” he said with characteristic self-deprecating humor. That sense of humor, sense of metaphor, and willingness to say exactly what he means, no matter what, make up the gist of Dave Morrison’s appeal as a poet.

“Words are the truer, deeper home,” he said.

SIDEBAR

Psalm 75

I think I am ready to

come home for a

while, to be attentive,

to do my work, to

ignore the moon and

the wind.

Thank you for not

locking the

door.