Imagine this. It’s winter. You’re up on a ladder, knocking icicles off your gutters, when a slight misstep sends you tumbling to the ground. You’ve fallen ten feet, and your head got a good knock on the frozen ground. Your partner calls 911, running outside with a blanket.

Everything hurts, and it’s hard to tell if anything is broken. The ambulance, staffed by two community volunteer EMTs and one driver, arrives about ten minutes later. They collect information about your fall and your medical history, check your vital signs, and do a head-to-toe assessment.

They put a cervical collar around your neck and immobilize you on an evacu-splint, which is then strapped to a backboard. They lift you, mindful to protect their own backs and knees, onto the stretcher, which has been rolled next to you. You’re loaded into the ambulance, where it’s at warm and the light is better.

You’re cold, you’re uncomfortable, and you’re frightened.

While the EMTs have been performing their assessments and interventions, the driver has been trying to arrange transportation.

It’s essential that you are taken to a hospital for imaging as quickly as possible.

And you live on North Haven, an unbridged island 12 miles from the mainland. That means, if the state Department of Transportation decides that Maine State Ferry Service boats will dock on the mainland for the night, as proposed, there will be no emergency transportation to a hospital.

The driver calls each of the few boat captains who keep their vessels in the water all year. Only one is available and willing to do the transport.

Back on the island, it’s 4 p.m., nearing dusk, and Penobscot Island Air is done flying for the day.

LifeFlight would love to help, but all its helicopters are out on critical calls, and because you’re breathing and talking and not disoriented, you’re not a high enough priority for them to redirect.

Driving the ambulance onto the ferry would keep you warm, and the EMTs would have access to all of their equipment should your condition change. It would also provide the most comfortable ride, as the wind has started to pick up.

But the ferry is docked on the mainland for the night.

The driver calls each of the few boat captains who keep their vessels in the water all year. Only one is available and willing to do the transport. She’s moored in the Fox Islands Thorofare and agrees to meet the ambulance at the town float in 15 minutes.

The ambulance backs out of the driveway and heads down the road. The driver is scrupulously careful, but each bump on the icy road sends shocks of pain through your body. The EMTs activate hot packs and tuck them in, wrapping you with several layers of additional blankets.

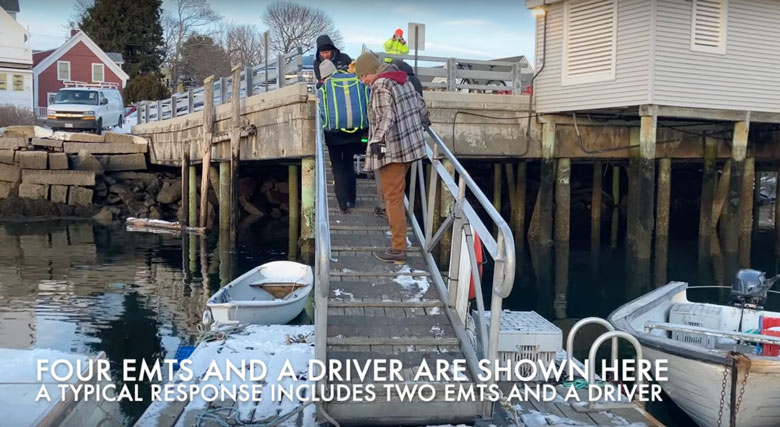

Upon arrival at the ferry parking lot, the ambulance driver backs as close to the float ramp as he dares. The EMTs and the driver hop out and open the back doors of the truck. The icy wind rushes in. They unload the stretcher and prepare for the treacherous descent down the ramp to the float.

It’s low tide, and the ramp is at a steeply acute angle. In the growing darkness, it’s difficult to tell which of the black tar paper steps are icy. The float looks like a sheet cake with a layer of white frosting, and it tosses and pitches atop the choppy water. As frightened as you are of the injuries you might have sustained, the next steps are even more terrifying.

The driver moves ahead of the EMTs to spot them as they head down the ramp. You can hear them narrating each step to each other as they move from the parking lot to the ramp, then the bump as the stretcher wheels are pushed and half lifted over each wooden strip. Your head is elevated, and your view is of the EMT at the foot of the stretcher. You can see the strain and worry on their faces as they use all their strength to keep the stretcher from tumbling out of control.

After an eternity—or a minute—the stretcher is off the ramp. You feel the movement of the float as waves of discomfort, and you can hear the wheels scratching on the crusted snow and ice.

The boat captain is ready and has hopped out of her vessel to assist with the next steps. You know her and are familiar with her boat. It has a partially enclosed cabin and an open stern, and you’re not certain how you’ll fit, mummified as you are. The wind cuts through the pile of blankets you’ve been swaddled with, and the hot packs are barely noticeable.

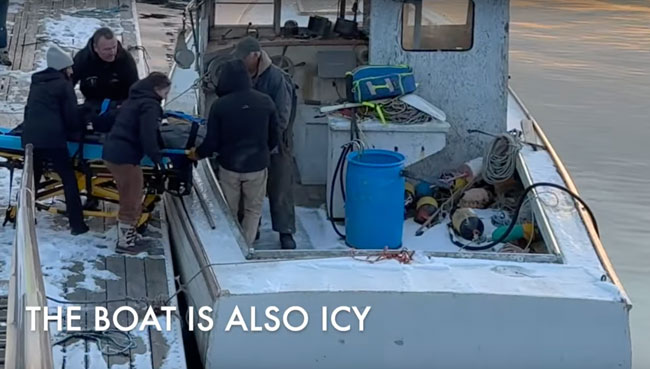

The EMT at your head narrates the next steps. First the stretcher is oriented perpendicular to the gunwale of the boat. You feel one layer of straps release around you. Then you’re slid halfway off the stretcher towards the boat.

The captain and the EMT at your feet climb into the boat, moving carefully as it, too, is encrusted with ice. You feel yourself sliding further towards them as the driver and the EMT at your head join them, hoisting you all the way into the boat as they climb aboard.

They carry you, avoiding coils of rope and plastic totes, as far into the partially enclosed cabin as they’re able to, and set you down on the count of three. The foot of the board, and your feet, are out in the open, and they add fresh heat packs and even more blankets.

They transfer essential equipment—a LifePack, a jump bag—into the boat. The driver disembarks to bring the ambulance back to the station and clean it, and the EMTs crowd into the cabin as best they can. One texts the crew members who aren’t on call to let them know that they’re both transporting, and to request coverage while they’re gone.

The boat pulls away from the float. You’re familiar with the route to Rockland, but you’ve most often experienced it from the relative comfort of the ferry cabin, or from your car on the boat. Your gaze here is on the ceiling of the boat. You can’t look at the horizon to stave off seasickness.

The EMTs’ faces come in and out of view as they make small talk, which you realize is both to distract you and to make sure you haven’t lost consciousness or become disoriented. The blood pressure cuff squeezes your arm at regular intervals.

The movement of the boat up and down over the chop increases, and you realize you’ve passed the Monument and are out in the open bay. The captain does her best, as the ambulance driver did, but time is also of the essence, and the EMTs urge her to sacrifice comfort for speed. The cold is dangerous, and the extent of your injuries are still a mystery.

The water calms. You’ve passed the Owls Head Light. You’re not sure if you can feel your toes, but when an EMT asks, you can make out the pressure of their hand on your foot. One of the EMTs radios to ask a mainland EMS service to meet them at Journey’s End marina.

The boat’s motor slows. The elaborate process of disembarking the boat begins. The captain and the EMTs lift you incrementally up and over the gunwale. EMTs from the mainland service walk down the ramp—easily three times as long as the one to the town float, and still at a dizzying angle—and assist in carrying you up. You can hear the squeak of boots as everyone struggles to maintain their footing on the slick metal surface.

Finally, you are loaded into the warmth and light of the awaiting ambulance, and you speed away to the hospital, not envying the captain and the two EMTs for their frigid ride home.

~ ~ ~

Although North Haven EMS utilizes private boats for emergency transportation regularly, we also depend on the Maine State Ferry Service for transportation where weather or patient conditions make it safest to have a warm, controlled environment with all of our equipment at hand.

Our transportation options also dramatically decrease in the winter, when many private boats are out of the water and daylight hours are diminished, making it more likely that we would need to ask for a ferry transport.

We recently filmed a demonstration of loading a patient on a stretcher from the ferry parking lot, down the ramp, and onto a lobster boat. We also filmed the reverse process, as though we had arrived at Journey’s End. It was mid-tide and perfectly calm, with the setting sun providing just enough light. At 25 degrees it was plenty cold, but we’ve seen single digit temperatures with negative wind chill factors this winter. Even in those relatively ideal winter conditions, a lobster boat ride strapped to a backboard isn’t something anyone would wish for.

The purpose of the demonstration was to advocate for the continued berthing of our ferries on the islands, which may no longer be the case in the near future.

We are always grateful to the private boat captains who are willing to run us across at odd hours and in challenging circumstances, but want to highlight the importance of having the ferry as an option, especially at night and in inclement weather, or when patient outcomes depend on having the resources and stability of the ambulance at our disposal.

The video has garnered hundreds of views, and our stance was highlighted in a Maine Public radio story. The discussion continues, but maybe putting yourself in the patient’s shoes is a helpful perspective to imagine.

To view the video, go to YouTube and search “Courtney Naliboff EMS transport movie.”

Courtney Naliboff lives with her husband and daughter on North Haven where she teaches in the island school. She also serves as a volunteer with the island emergency medical services team.