When I moved to Portland in 1988, I did not come alone: hundreds, perhaps thousands of images tagged along providing me with a vivid mental map of this place where place still matters. Rocky coasts, lighthouses, and lobster rolls, of course, but also quaint downtowns of white clapboard houses, shade trees, and assorted shops run by old salts and hardy women.

As a labor historian, I knew the sorry limits of these colorful images especially in Maine, where the wrecking ball of deindustrialization had been gathering devastating traction for years. A bitter strike at the Androscoggin paper mill in the northwestern woods of Jay was still fresh in public memory as were stories of Jesse Jackson, who had come to Maine on behalf of the strikers to draw a line in the sand. Enough!

But it was not the class divisions or Jay strikers that rose up in the national imaginary that year. It was Murder She Wrote.

Beginning in 1984, and continuing for 12 seasons, Angela Lansbury (as Jessica Fletcher) solved countless murders in a small Maine hamlet called Cabot Cove. Even as the town became the murder capital of the United States, its quaint olde shoppes, old-timey folks, charming cafés, and biking simplicity, reinforced prior cultural images that established Maine coastal towns as the quintessential New England.

According to the Maine Turnpike information center, the question most frequently asked in 1993 was, “Where is Cabot Cove?”

Like Robert Frost, coastal Maine towns grew Yankier and Yankier, as more than 30 million viewers tuned in every week to embrace a mythical lost past and nostalgic authenticity. According to the Maine Turnpike information center, the question most frequently asked in 1993 was, “Where is Cabot Cove?”

Where indeed?

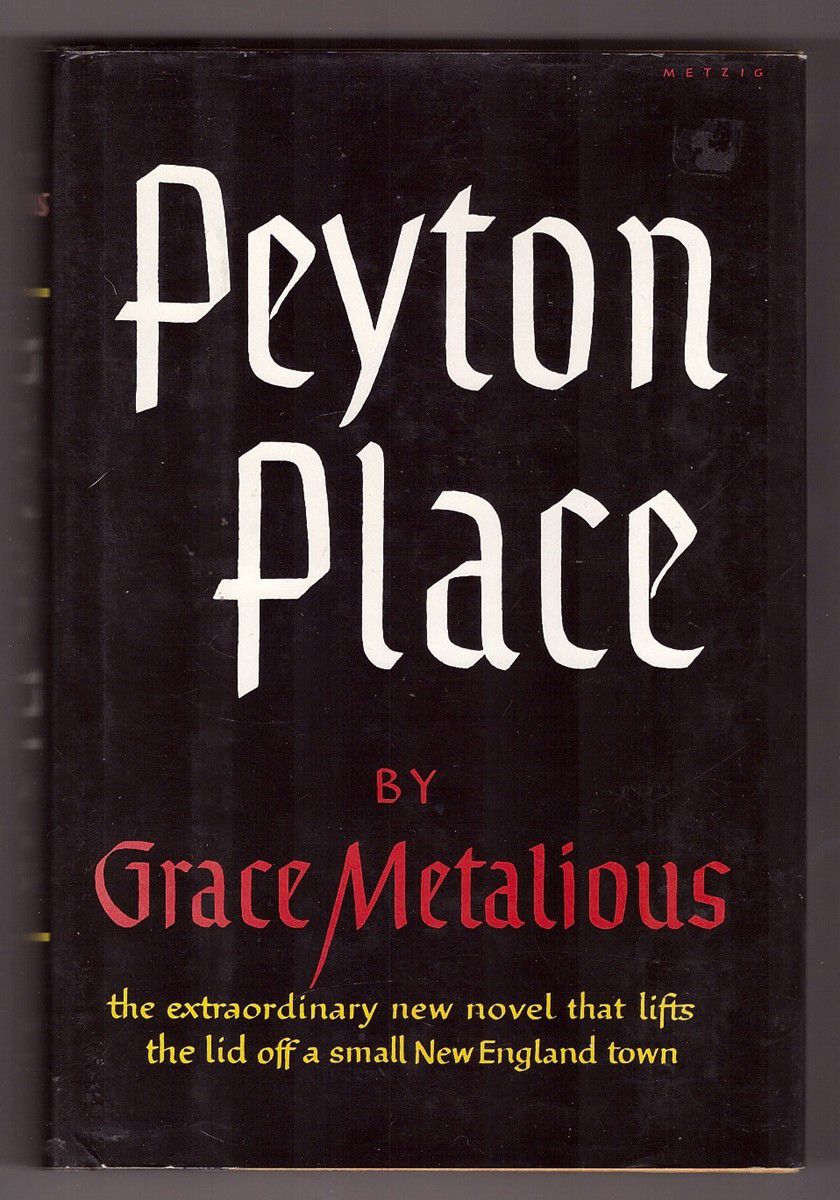

While Murder She Wrote sent thousands of tourists in search of the picturesque, my students sent me inland to a town called Peyton Place. Published in 1956, the novel Peyton Place took readers off road into a sexualized world seldom associated with New England. Located in a small New Hampshire town, Peyton Place is based on a true tale of patricide, involving a young girl who had been sexually abused by her father for years.

Written by Grace Metalious, the young wife of a local school principal, it took off like fireworks, bringing the open secrets of incest, homosexuality, and abortion into sharp national relief. In an age when the average first novel sold 2,000 copies, it sold 60,000 copies within the first ten days. Soon, it would become the fastest selling book ever published and the best-seller of the century.

A “Canuck” to her Yankee neighbors (French was her first language), married to a Greek-American, Grace Metalious purposefully set her New England in sharp contrast to the one seen through the “rose-colored spectacles” of other writers.

“New England towns are small and they are often pretty,” she explained to reporters, “but they are not just pictures on a Christmas card. To a tourist these towns look as peaceful as a postcard picture, but if you go beneath that picture, it’s like turning a rock with your foot—all kinds of strange things crawl out.”

While critics split over the merits of the book, thousands of readers felt empowered by a story that finally reflected their lives. Hundreds wrote the author to let her know. “Your characters are all true to life!” a New Hampshire woman wrote. “One of them is my uncle!” “I live in Peyton Place,” a Belfast woman told Grace. And not a few saw redemption in the tale. “I had an abortion too. Thank you for pleading my case.”

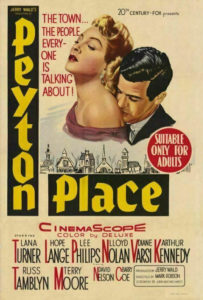

But neither the town of Peyton Place nor its bankrupt residents stayed in New Hampshire for very long. In 1957, Hollywood moved them to Camden where the story underwent the first serious defanging. What to letter writers had been a welcoming airing of “long-buried facts in the countless graveyards of New England,” was uplifted into a “cleaned up” story where strong women fall into line under the direction of the film’s writers.

Tar-paper shacks receded into the tree-lined streets and handsome white houses of coastal Maine. The central character, Selina Cross, becomes Yankier and Yankier, her “dark, gypsy’ features morphing into the blond, blue-eyed figure of starlet Hope Lange. While the rape is brutal and the abortion is performed, Selina becomes a romantic victim rather than the courageous and strong-willed girl who defied the town and succeeded on her own merits. “Andy Hardy could have lived here,” the New York Times critic snorted in contempt.

By 1964, when the television show aired, Peyton Place grew downright respectable. Drunks sobered up (or became middle-class) while the town became a cliché of New England kitsch. “It has,” a reviewer noted in 1965, “no discernable Negroes, no obvious Jews, no bigotry, no religious or political divisions.”

Abortion, incest, and child sexual abuse disappeared, the very idea pushed beyond the realm of the imaginable. A perfect place, in other words, for the future television sleuth and mystery writer Jessica Fletcher to call home. In the popular imagination of national television, murder was just fine, but abortion, incest, and sexual abuse were erased, put, once again, beyond words. They did not happen in America’s Cabot Cove.

Peyton Place is based on a true tale of patricide, involving a young girl who had been sexually abused by her father…

I was asked to write this piece because it is the 65th anniversary of the film and perhaps nothing put the Maine coast on the map more than Peyton Place. But as I write, the Supreme Court has sought to set our clocks back to another television age when fathers knew best, housewives were white and stayed happily at home, incest was a myth, abortions never happened, and books like Peyton Place were banned. With Dobbs v Jackson, the reality of women’s lives is once again erased; their right to make decisions over their own reproductive lives, denied.

The cultural battles over representation in general, and Peyton Place in particular, may seem trivial to more explicit wars over values, beliefs, and identities. But they are not. Rather, as Grace Metalious understood, and many readers discovered, if we can’t imagine the trauma of unwanted pregnancy or the abuse young girls and women face in our own backyards, then we will remain powerless to stop it.

From the letters readers sent to Grace Metalious, we can see the depth of emotion her story of incest, rape, and abortion aroused and the hopes her female characters put into play, and the pain and longing that echoes down to us still.

As The Working Waterfront has long made clear, coastal Maine is complex and far more diverse than outsiders might imagine. Challenges abound. Yet, confronting change means understanding that images of people and place are always at work normalizing this and demonizing that, or just plain erasing what doesn’t fit into the postcard pictures of Maine.

Ardis Cameron is professor emeritus in American Studies at the University of Southern Maine. Her most recent book is Unbuttoning America: A Biography of Peyton Place. She lives in Stonington and South Portland.