Seawall Beach and Picnic Area, which was severely damaged by winter storms in 2024, is named for a natural formation resulting from interaction between land and sea. Not to be confused with constructed “sea walls” of concrete, Seawall Beach and other features known locally as sea walls are steep beaches and ridges of cobble and boulders.

In 1861, Ezekiel Holmes and Charles H. Hitchcock described Seawall Beach as “a form of coarse drift” in their preliminary report on the natural history and geology of Maine:

“[Seawall] consists of a long embankment of smooth boulders, without gravel, arranged on the seashore at high water mark. When the great storms in the spring prevail off the coast, very powerful waves transport from the bays multitudes of boulders, some of them a couple of feet in diameter, as far as their agency extends.

“Hence, the work of years has accumulated in various places quite large embankments, which are popularly called sea walls. They are often shaped like the glacis of a fortification, the side next the sea having a small slope, and the side next the shore being quite steep. The sea wall in Tremont is at the Southwest Harbor. It is often 15 feet high and over a quarter of a mile in length…”

Like sand dunes and salt marshes, sea walls protect coastal property by bearing the brunt of storms. And like a sand dune, sea walls are always shifting as waves and tides push the rocks around. This usually gradual process of shaping becomes dramatic during storms, when large waves pick up rocks from the base of the wall and carry them to the top.

The size of the rocks shows the energy of the waves that created the wall, as stronger waves can transport larger stones to the top of the pile, where their weight keeps them in place as smaller pebbles tumble back to the bottom with each receding wave.

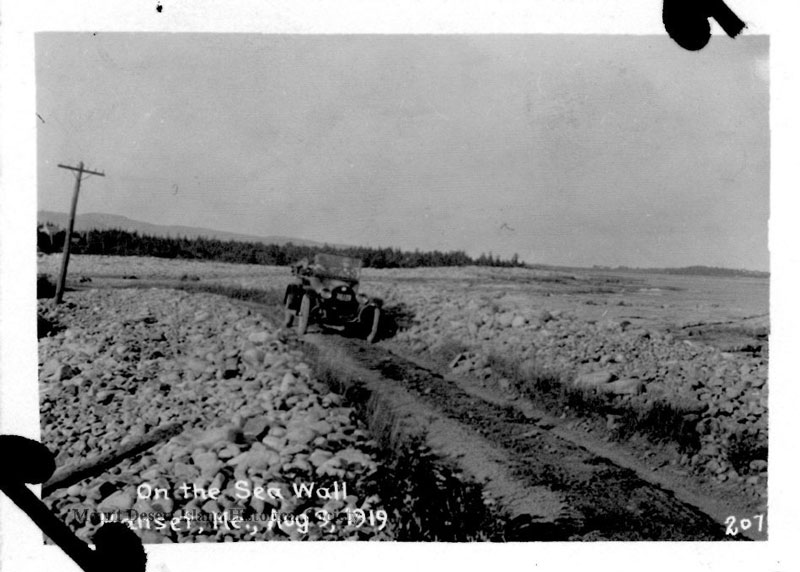

Historically, sea walls created a logical pathway for navigating the shoreline. Foot trails tracing the top of the “wall” became cart paths and roads traveled by tourists. The Mount Desert Herald reported in November 1882 that George Kelley had finished building a “good road” running from Seawall to Bass Harbor, via Ship Harbor, “making the border road of the island complete.”

The Mount-Desert Guidebook described Seawall in 1888 as:

“a rampart of stones and rocks, ranging in size from pebbles to boulders, and stretching for a long distance between the low green meadows on one side and the resounding sea on the other. It looks as if it had been built by benignant giants, to keep the whitening waves from the green fields inside, which would else be overflowed by many a furlong. But all this titanic work has been done by Neptune himself, in times of storm smashing the submarine ledges outside, and throwing their fragments high up on this adamantine barrier…

“Here, also, the sea breaks with greater power and eloquence than anywhere else in this region; and parties often come picnicking to the ledges, to the see the majestic sheets of white spray that dash over the rocks when a heavy sea is on. The road follows the rugged crest of the Sea Wall, for a mile, in places as high above the land as are the dikes of Holland, with spruce trees occasionally coming down to the edge of the rocks, and peering into the turbulent waves…”

Scientist Roy Waldo Miner noted the role of storms in both forming Seawall Beach and destroying the road atop it in 1922, writing in Natural History:

“[It] is a natural wall or embankment consisting entirely of small, sea-rounded bowlders, which have been cast up during the winter storms to form a rampart several hundred feet in length and a dozen or more in height. A road crosses this rampart obliquely, but is obliterated by the storms each winter and the following year has to be reconstructed.”

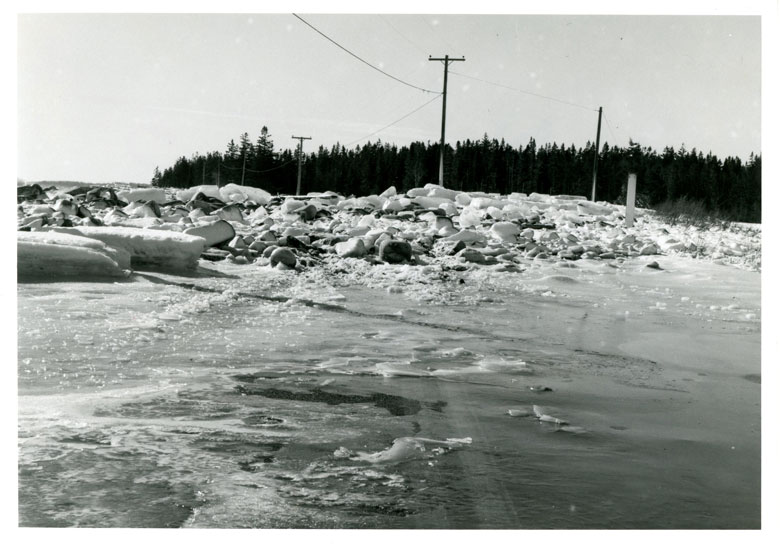

Acadia’s sea walls have always been pushed around during storms. An undated photograph by LaRue Spiker shows snow and ice-encrusted rocks strewn over the Seawall Road. Today, sea level is nearly one foot higher than it was in 1950. Waves and storm surge are higher and reach even farther inland. During storms, sea walls roll over into back barrier lagoons and wetlands. At Seawall Beach, and along the Schoodic Loop Road, this means repeated damage to roads. Roads also restrict drainage between the ocean and ecosystems behind the barriers.

A sea wall’s mobility is easier to visualize in areas where there is no road to impede it, such as West Pond on the west side of Schoodic Point, or between Ship Harbor and Wonderland on MDI, where waves during the January 2024 storms carried rocks over the back of the sea wall into the alder swamp on the landward side.

Seawall Pond is a similar back-barrier wetland that has always been exposed to salt spray and occasional inundation.

The pond drains to the sea via a culvert beneath Seawall Road, and water levels fluctuate. The National Park Service has been monitoring water quality in Seawall Pond since 2007. Conductivity, a measure of the concentration of ions or salts, is orders of magnitude higher in Seawall Pond than in other lakes in Acadia, and it’s highly variable, suggesting varying degrees of marine inputs. Seawall Pond (labeled as Seawall Swamp on some early maps) is relatively productive, with consistently high nutrients and chlorophyll, likely due to the pond’s small size, shallow depth, and abundance of gulls and waterfowl.

Sea wall ecosystems are dynamic landscapes that challenge ideas of permanence, despite protections afforded by being in a national park. A 2017 assessment rated Seawall Picnic Area as highly vulnerable to hazards and climate change. The report also noted that while the hydraulic energy of the waves at high tide presents management issues, the tremendous force of the waves is also what created Seawall, Thunder Hole, and other unique features that define Acadia.

As told by the National Park Service, “Acadia’s cobblestone beaches are some of our most treasured gems for their striking beauty and charming rattling in the waves. The stones also tell the stories of countless rock formations that have traveled to the beach by means of glaciers and ocean currents. These rocks can be traced to areas all over the region, frequently starting as much larger glacial erratics. The stones are pounded by waves over years and years, through nor-easters and storms. They are smoothed out over the relentless shaping of the waters and collisions with other rocks. The rugged journey and significance behind each cobble makes their protection a priority.”

As we enter a season of exceptional high tides or “king tides,” we will be monitoring Seawall and other locations to learn how changes to the shoreline from last winter’s storms may have affected tidal flooding. You can join us by posting water level observations to the Gulf of Maine King Tides project.

Catherine Schmitt is a science communication specialist with the Schoodic Institute.