Life on the northern frontier is not for the faint of heart. The extreme environment has shaped those who have called the Arctic home for thousands of years and has inspired myth and folklore. The stories have taken on a life of their own with a darkness reminiscent of the polar night.

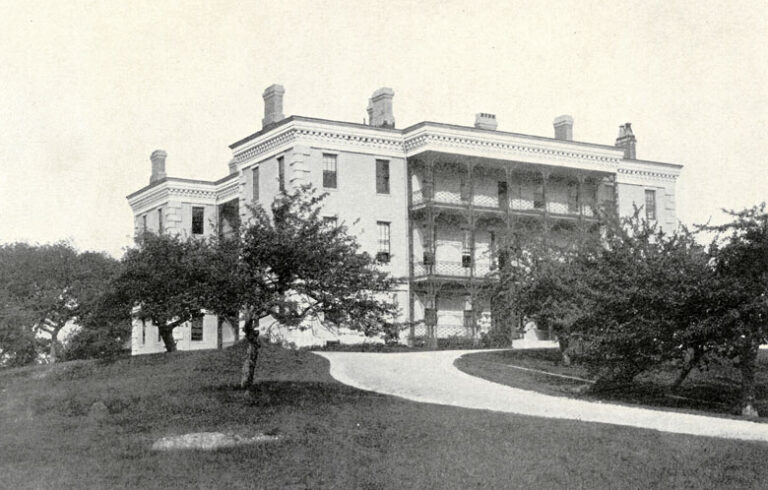

The newly constructed Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum at Bowdoin College in Brunswick features the exhibit “Northern Nightmares: Monsters in Inuit Art” through May 2025, offering a glimpse into this dark side of Inuit mythology.

From Alaska to Canada to Greenland, the origins of these mythical figures vary depending on their location and the diverse cultural characteristics of each Inuit community. The sense of spirituality imbued in Arctic lands and waters, however, is shared by all. It is this otherworldly presence that has given life to these haunting figures in stories that have withstood the test of time.

The creatures in these stories are often inspired by encounters with danger in the Arctic wilderness. Some of the stories offer guidance on proper social behavior and warnings for survival to ensure children do not wander too close to the edge of the ice, for example.

In Alaska, some figures were painted on kayaks to ward off danger, including palraiyuk, a lizard-like creature with sharp teeth and multiple stomachs (filled with human limbs) who lurks in shallow water to devour people at water’s edge.

Some are origin stories and may tell the tale of people who have cleverly overcome peril, including the story of how fog came to be from Nunavik, Canada, in which a man-eating giant was outsmarted by a hunter who was about to be eaten for dinner.

There are some stories that would likely mystify those outside the culture and not offer up perceivable morals. Naalikkaatseeq of Greenland is known as “the eater of entrails” because she intercepts angakuit (shamans) traveling to visit the Man in the Moon and fulfills her promise to eat their entrails should they smile or laugh during her dance performance.

The mystery of these figures is not locked in the past and continues to evolve within and beyond contemporary Inuit culture. The 20th century gave rise to a new wave of Inuit artists who moved beyond traditional folklore, inspired by increased contact with the world beyond the Arctic.

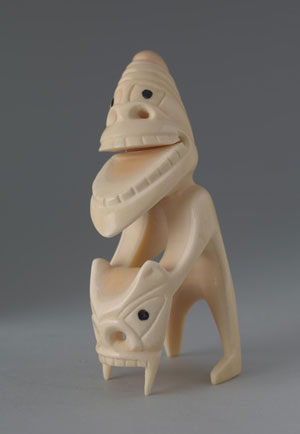

Genevieve Lemoine, curator at the Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum, said the evolution of the tupilak—a monster or a carved replica of a monster—from Greenland is one of the ideas that became a source of inspiration for this exhibit.

“The tupilak is a very interesting story,” she explained. “What is a ‘real’ tupilak, so to speak? How have they evolved in Greenlandic art? The shift has been surprising.”

Historically, a tupilak spirit was called upon to help against a foe by a shaman who secretly created a grotesque figure from bones and parts of animals, which became a home for the malevolent spirit after a spell was cast over it. The tupilak was then released into the world to find the enemy and kill him; however, if the tupilak’s victim had greater powers than its creator, the attack could be repelled and the tupilak would be sent back to kill its originator. After the task was accomplished, the tupilak ceased to exist.

As more Europeans explored eastern Greenland in the 20th century, the demand for depictions of the tupilak began to grow and resulted in carvings made from wood, bone, tooth, horn, and antler. The more grotesque the carving, the more popular it was among western buyers, who were enchanted by the grimacing, skeletal figures. Over time, local artists developed their personal style and carved a variety of beings from their old stories, which were then marketed by companies as tupilaks to appeal to buyers.

In recent years, tupilaks have evolved to meet demand and are being carved from antler, bone, soapstone, stone and wood for the tourist market because whale tooth may not currently be exported. Perhaps more surprising, however, is the shift in meaning. Tupilaks are now being interpreted in modern artistic expression and sold to tourists in souvenir shops and airports as sources of protection, a far cry from their origins as a malevolent spirit meant to inflict death.

No matter how these myths and meanings evolve, one thing is certain, says Lemoine.: “Everyone has nightmares.” She hopes to feature Greenlandic horror films, among others, during a cinematic showcase in connection with the exhibit.

Admission is free at the Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum at Bowdoin College in Brunswick. Hours are: Tuesday-Saturday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., and Sunday 1-5 p.m. To learn more about it other exhibits, see and bowdoin.edu/arctic-museum.