It’s hard to imagine a heavy tar sands oil spill in the Gulf of Maine. Not just because of the vastness of the open ocean and our dependence on clean water for our fisheries economy, but also because tar sands oil is mined and steamed from the ground thousands of miles away.

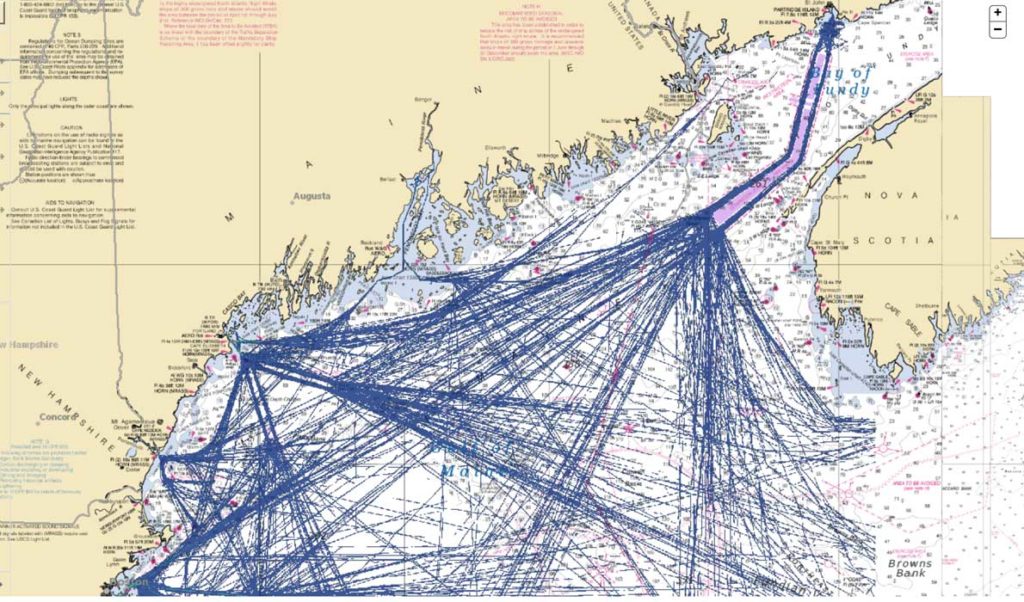

However, there is a proposal in the works in Canada to build a pipeline all the way from the tar sands deposits in northern Alberta to Saint John, New Brunswick, through which tar sands oil, in this case diluted bitumen (known in the biz as “dilbit”), would be transported. An estimated 281 oil supertankers per year would then transit the Bay of Fundy and the Gulf of Maine, delivering primarily dilbit to refineries in the Mid-Atlantic and Gulf Coast regions, essentially creating a floating pipeline over some of the nation’s most productive fishing grounds and critical habitat for marine life.

If increased oil transport in the Gulf of Maine isn’t concerning enough, dilbit happens to differ chemically in a major way from conventional crude oil: it cannot effectively be cleaned up when spilled in water. Dilbit is a manufactured combination of extra-heavy bitumen, with the consistency of peanut butter at room temperature, and a much less viscous diluent.

The mixture allows it to be moved through pipelines, but most of the diluents used are highly volatile. Immediately following a spill, rapid evaporation of the diluent can produce a dense residue in a day or so.

Conventional crude oil behaves differently. Its light components evaporate more slowly and the eventual residues are seldom as dense as those resulting from tar-sands bitumen. Particularly when mixed with sand or silt, dilbit residues are far more prone to sink than are residues of conventional crude oil. Also, its ability to stick to other objects, or its “adhesion,” is up to 100 times greater than that of conventional oils. Thus, sticky, tar sands oil, with its propensity to sink, poses a substantial, long-term, risks to life on the sea floor.

The important point for coastal communities adjacent to the potential transit route of dilbit is this: spill response techniques for non-floating oil in water are inadequate. That is one conclusion of a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report, “Spills of Diluted Bitumen from Pipelines: A Comparative Study of Environmental Fate, Effects, and Response,” published earlier this year.

Several factors complicate the response to a diluted bitumen spill. Immediately after a spill, weathering (the physical and chemical changes of spilled oil) happens quickly and the window during which dispersants, burning or containment techniques could be used is very small, thus increasing the likelihood of submerged and sunken oil.

The NAS study argues “there are few effective techniques for detection, containment and recovery of oil that is submerged in the water column, and available techniques for responding to oil that has sunk to the bottom have variable effectiveness…” Add to this the complicating factor of mustering a response in an open ocean environment, and those recovery and containment techniques look even less feasible.

Dr. John Hayes, an author on the report, noted, “Even if we were totally prepared to clean up a conventional oil spill, this is a different matter and bears reconsideration of our preparedness.”

Hayes, an organic chemist and marine scientist and member of the National Academy of Sciences, pointed to lessons learned from a spill in Michigan’s Kalamazoo River where dilbit residues sank much more rapidly than spill crews expected. It took years to clean the bottom of waterways there.

We don’t have much experience with dilbit spills in marine environments, not because of an exceptional safety record, but because there isn’t much transport of dilbit over the ocean. The Exxon Valdez and Deepwater Horizon spilled conventional crude oil. And in the case of Alaska’s Prince William Sound, over 27 years later, crude oil can still be found buried in the sands of many beaches. Burnaby, British Columbia and Santa Barbara, Calif. both have had instances of heavy oil reaching coastal zones, but only in estuaries or very shallow coastal waters, allowing response strategies such as vacuuming, booming and manual removal to be immediate and somewhat effective. In both cases, even with the spill confined to nearshore, sunken and submerged oil adhered to kelp beds and nearshore reefs.

Clean-up approaches for spilled dilbit are based on conventional floating crude oil, and there is no known effective technique for recovery of submerged crude oil, especially in an offshore environment. Particularly for people in the region who rely on clean water for their livelihoods, the proposed pipeline and shipping of dilbit through the Gulf of Maine is worth tracking.

Dr. Heather Deese is the Island Institute’s vice president of research and strategy. Dr. Susie Arnold is an ecologist and marine scientist with the organization.