This is the second of a three-part series recollecting the look and feel of Portland in the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s by a Maine writer who spent his youth there.

In the 1970s, Portland grew up.

That’s one way, anyway, of describing the transition the whole city, and especially the Old Port neighborhood, made from being a backwater in the 1960s to a trendy waterfront destination by 1980. And two main factors drove it: money and art.

In the ’60s, a big question looming on the minds of the town fathers was how to lure tourists off the Maine Turnpike gangway and into the city. One practical way was to build a road. So a spur was planned to take autos piling in from Massachusetts and Connecticut directly to downtown. The I-295 veered off the Turnpike near the newly open Maine Mall in South Portland, crossed the Fore River, curved past UMPG’s cozy little Portland campus and Back Bay, then merged with Washington Avenue and went on to Falmouth.

The most direct route into downtown was off Marginal Way and up Franklin Street, which was cleared out in the late 1960s and urban-renewed into a four-lane artery emptying onto Commercial Street. When the spur opened in 1974, the tourists could drive straight to the Old Port.

But why would they want to? That neighborhood was still part of a rough and tumble sort of working waterfront. Joe and Nino’s Circus Room lurked prominently on Middle Street. Eddie’s Shamrock Cafe at the corner of India and Commercial was another place you could get knocked around.

In the early 1970s, though, that roughneck character was changing. Artists, musicians, artisans and other cultivators of counterculture were setting up shop in cheap digs and creating a sort of toy Greenwich Village. In the spring of 1973, two young friends of mine rented a storefront at 372 Fore Street for $75 a month and ran a Maine-made gift shop. Within weeks, the landlord wanted to double the rent, so after a few months they closed. Next door, Richard Julio fought to keep the original rent for his used record shop, The Wax Museum. He, too, soon vacated.

If you were in the area often—say, to go to Books Etc., Metanoia Books (esoterica on the second floor at 31½ Exchange St.) or Carlson-Turner Books at their original down and dirty spot on Milk Street (decades before the park and its syphilitic dolphin)—you came to recognize the resident artists, like Lenny Hatch, Steve Priestly, and later on, Phil Poirier. And before David Koplow, the infamous Dog Man of the 1980s, there was Reggie Osborn, an itinerant actor, with his adopted dog Filé, a stray who befriended strangers ubiquitously on the peninsula, including in the Good Day Market neighborhood on Brackett Street. Everyone recognized Filé and Reggie, whose ebullient smile lit up whole city blocks.

Reggie was a one-man figment of 1970s Portland, an emblem of the energy complete strangers were feeling. Sometime in 1975, an arts-struck letter-writer to the Portland Times weekly (which made a news splash for three energetic months)—or maybe to the USM Free Press—declared in a fit of hyperbole that Portland was “the Paris of the ’70s.” Well, we college students had some sardonic jokes about that phrase, but it echoed in our conversations because we felt it too.

PORTLAND UNDERGROUND

The University of Maine at Portland-Gorham was my arterial into Portland’s underground arts scene. (My first year, 1971-72, I paid the $175 per semester tuition by squirreling away the $1.65 an hour I made working weekends at Smaha’s Legion Square Market in Knightville.) One day the already-notorious poet James Lewisohn was handing out copies of a new Portland-based small magazine, Contraband, in one of his literature classes. This unfolded into as big a moment for me as my teenage hours combing the Paperback Book Store on Congress Street.

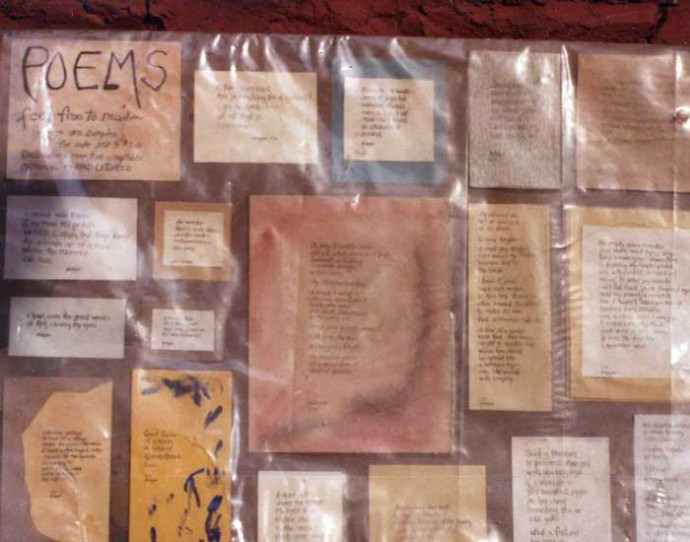

I wrote to the editors, and by 1975 was visiting Bruce Holsapple in front of the old Portland Public Library, where every sunny day he set up an easel to display calligraphied copies of his poems, and talked about poetry and art with whomever happened by. Artist Michael Waterman, it might be, or poets like Scott Penney and Peter Kilgore who helped produce Contraband—Maine’s most significant contribution to the literary counterculture—out of Bruce’s top-floor room at 85 Park St.

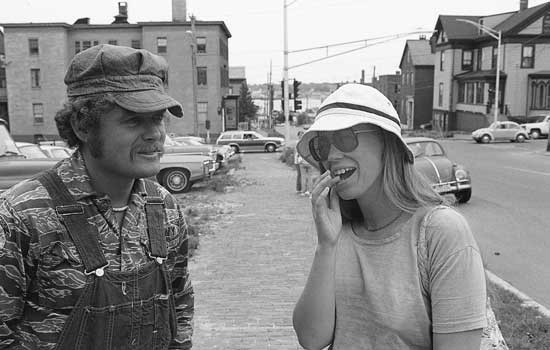

PHOTO: JOHN DUNCAN

Munjoy Hill in 1973.

Meantime, hours were whiled away at drunken parties with USM and Portland School of Art students, and at bars among the city’s knockaround poets and musicians. After classes we’d hit the Forest Gardens near campus. One night there, I had a long fascinating talk about music with the young WLOB-AM radio DJ Bill O’Neal. In the summer of 1974 we attended every Tuesday night Kotzschmar Organ concert at City Hall (free). In 1975, for $5, first balcony rail, we saw Tom Rush. In the basement cafeteria of USM’s Payson Smith Hall, Devonsquare.

Our Paris of the ’70s nights were spent at mainstay establishments like The Bag and the raucous Free Street Pub. In the Old Port, Joe and Nino’s got converted into the city’s first full-on disco in about 1976. I got confused when a guy at the bar was sending me beers.

The logo from Jim’s Bar & Grill

Nearby Boss Tweed’s in turn became The Sun Tavern, where we listened to music and argued about poetry and art (“come off it, the Impressionists are just eye candy”; “Well what about John Marin, then?”) and listened to a friend’s tales of picking up Harlan Ellison hitchhiking.

In 1976, Jim’s Bar and Grille opened across Middle Street, where music was played and poetry was sometimes read. One night an agitated, drunken cargo sailor took offense at Holsapple’s grueling introspections and shouted, “Why can’t you write about something cheerful, like flowers?” Zamrath the Magician made the rounds of the tables.

RISING RENTS

As the Old Port bubbled, rents rose through the 1970s but were not yet exclusionary. The neighborhood could still be rough. The Post Office Plaza park between Market and Exchange Streets was still a parking lot surrounded by a barbed-wire-topped chainlink fence. In 1976, the lawyers at Verrill & Dana, where my mother was a secretary, took turns on winter evenings protectively walking the female staff from the office on Exchange and Middle to their cars in the Pearl Street lot. Around 1975 or ’76 we got the city’s last 10-cent draft beer at Eddie’s Shamrock Café—in the safety of late afternoon.

In Mul’s Irish Pub on Middle Street, c. 1978, the floor creaked under dancers. In the Deli I on upper Exchange, our band of choice was Franklin Street Arterial; jazz on afterburners those guys played, sometimes with a completely bonkers young conga drummer. The band’s torrid sax player later opened a music shop just up from Congress Square—Crazy Ed’s.

By 1977 or so, artists and Kerouackian culture poseurs who’d heard Portland was a makeable scene were coursing in. Some of them lingered for years. We observed that Portland often got its hooks in people and didn’t let go.

And for those of us whose histories antedated I-295, the backwater past lingered.

Gill’s Handy Store on Spring Street, 1970s. PHOTO: AUTUMN RIDDLE

When I was a young teenager, we’d made mean fun of the Hobby Center elevator operator with his withered arm and garbled speech. Ten years after, he re-appeared in the USM Portland campus library. His job was checking backpacks (in those days, they checked you on the way out for stolen books, not on the way in for bombs). His name was Donald G. Conant, and he had written and published a book of poems which he kept for sale beside him at his library post. I bought one.

The seemingly handicapped past speaks poetry, it turns out. You can’t always hear it while it’s happening.

Bruce Holsapple’s easel board of calligraphied poems in front of the old Portland Public Library on Congress Street. PHOTO: BRUCE HOLSAPPLE

One summer night in 1975 or ’76, I was sitting in the new little park at Spring, Middle and Temple streets beside the rejuvenated Maine Lobsterman statue. Across Temple was a rusting piece of jagged something (named “Michael”) that spurred constant arguments among us about the purposes of art. Nearby, the Shot in the Dark gallery—in what would become the Barridoff Gallery—was projecting slides across Spring Street onto the whitewashed wall of a Union Street tenement. The air was warm, humid, thick with floating seed pods of invisible possibility. “Paris of the ’70s!”

But behind it, another world was rising. Construction was under way, just across Middle Street, on a multistory office building. Portland was being transformed into Boston North.

Money was coming. And its complications.

Dana Wilde of Troy is a columnist, editor, Fulbright scholar and former college professor. He writes the Backyard Naturalist column for the Kennebec Journal and Morning Sentinel newspapers, centralmaine.com. His next collection of writings on Maine’s natural world, Summer to Fall, is due out later this year from North Country Press.