When we think of Maine’s working waterfront, images of lobsterboats, stacks of traps, busy wharves, tied-up dinghies, and the like are apt to come to mind. The printmaker Pauline Winchester Inman (1904–1990) found these subjects in the 30-plus summers she spent in South Addison and turned some of them into the finest kind of art.

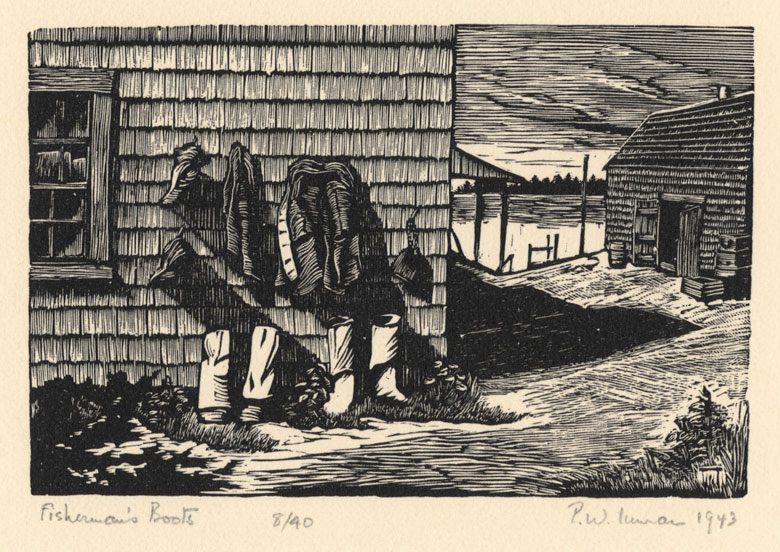

In “Fisherman’s Boots,” 1939, a print she also titled “Maine Coast,” Inman focused on the garments of a Downeast fisherman. She let the knee-high footwear, waterproof jacket and pants, and sou’westers stand in for the figures who frequented the docks, loading and unloading boats, preparing to spend another day on the water.

There’s much to admire in this wood engraving. Consider the rows of weathered cedar shingles on the fish houses, the lengthening shadows, the boots that seem to light up in late-day sun. It’s a landscape as still life—and vice-versa.

Consider the rows of weathered cedar shingles on the fish houses, the lengthening shadows, the boots that seem to light up in late-day sun.

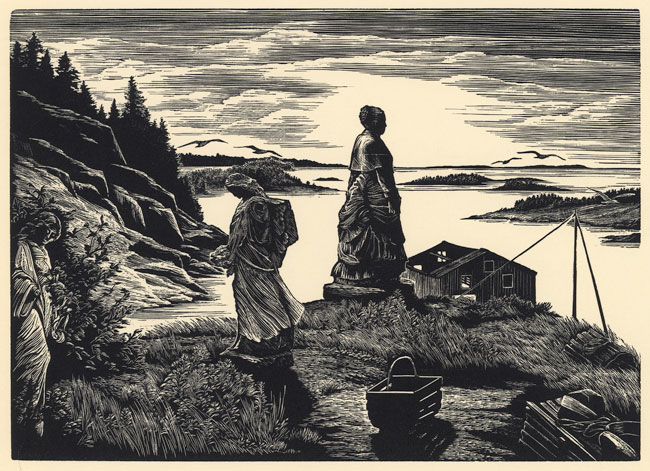

In another print, “Abandoned Quarry,” ca. 1956, Inman pays tribute to the Downeast granite industry, which began to fall on hard times in the 1920s. In her haunting image, three carved female figures stand atop a coastal bluff overlooking a destitute quarry building. It’s a brilliant rendering: the women, the gulls floating on the wind, a wooden clam basket—even the grasses and foliage—are precisely incised.

From sketches made and photographs taken during the summer, Inman would engrave the wood blocks at her winter home in Newtown, Conn. Her Maine motifs included Downeast homes (including the Ruggles House in Columbia Falls), a bait boat, blueberry barrens, and village scenes, including a cake sale. She also engraved images of New York City and Nova Scotia as well as Newtown, where she died on Jan. 16, 1990.

The Chicago-born Inman studied art history at Smith College, graduating in 1926. She went on to teach in New York and develop an art practice through classes at the Art Students League, the Parsons School of Design, and the New School for Social Research where she studied printmaking with Allen Lewis (1873-1957). Inman also worked in publishing, illustrating books and articles for Down East, Artist’s Proof, and Antiques Guide.

Inman belongs to a diverse and exceptional line of printmakers who have found inspiration in Maine, from Frank Benson, Ernest Haskell, Rockwell Kent, Stow Wengenroth, Carroll Thayer Berry, and Peggy Bacon to Thomas Cornell, Marvin Bileck, Holly Meade, Alison Hildreth, Susan Groce, and Siri Beckman—to name (quite) a few.

The Tides Institute and Museum of Art is committed to bringing to light the cultural history of greater Eastport. “Home, Downeast: Wood Engravings of Pauline Winchester Inman,” on display last summer, exemplifies that mission, introducing a new audience to the work of an exceptional artist immersed in the region. Kudos to Hugh French and his staff for their dedication to curating the past into the present.

Inman’s papers are held by the Archives of American Art and the Women Artists Archives National Directory. In addition to the Tides Institute and Museum of Art, the Farnsworth Art Museum, Library of Congress, Metropolitan Museum of Art and Philadelphia Museum of Art have significant collections of Inman’s prints.

Carl Little is the author most recently of Blanket of the Night: Poems (Deerbrook Editions) and the monograph John Moore: Portals (Marshall Wilkes).