Early in 1977, another new restaurant opened in the Old Port. This one on Middle Street had a tongue-in-cheek sign: “Carbur’s: Since 1977.” A tradition going all the way back to this year! Hilarious!

The Cumberland County Civic Center opened then, too, a shrewd public-finance deal. In 1979, the Portland Public Library moved from the stately old Baxter building at 619 Congress Street to its glassy new square-panel home off Monument Square. In 1981, down came the somewhat ungainly, yet visually lovable landmark Libby building on Congress Square, in favor of an I.M. Pei & Partners-designed façade for an addition to the Portland Museum of Art. Progress!

The late 1970s was a pivot point for Portland. Out of Phase 1 of a cultural resurgence in the 1960s to mid-’70s, Phase 2 barreled across the ‘80s and, I guess, the ‘90s, ‘00s and ‘10s where it turned into Phase 3, 4 and 5, I don’t know. By 1988, I was gone.

Up to then, Portland was decidedly home. It had come to me like a ton of bricks one epiphanic December morning in 1977, in front of the Spring Street Greyhound station, that I loved the immanent physical place I’d spent much of my naïve youth feeling disaffected about. I and the city were turning a corner.

This must sound like I probably cheered enthusiastically for the museum additions. Who could possibly have been opposed to ditching the old Libby edifice in favor of an “architectural wonder,” as it’s since been described?

Quite a few people, actually.

The architects’ word “façade,” I mean, became central to a joke we repeated in different ways on the street. Was it still an art museum, or was it just trying to look like one? The Libby building, at least, looked like what it was, and did it pretty well. But forces were working hard to turn reality into appearance.

By 1980, rents in the Old Port were climbing out of reach for those of us off the financial radars. New rules restricted what signs shopkeepers could hang on Exchange Street. Mr. T’s sandwich shop got a pass for a while, then closed.

As the neighborhood upscaled, the arts and culture wave that made the Old Port a destination crested.

MUSICAL EXPLOSION

In the early ‘80s a mini explosion of local bands blasted Portland’s version of energetic, edgy New Wave rock and roll in places like the Free Street Pub, Kayo’s (previously Mul’s) and the Rathskellar, both on Middle Street, Zootz on Forest Avenue (near the site of the old Pagoda restaurant), the Downtown Lounge on Preble Street, dim, dark Geno’s on Brown Street, and then the ambitious Tree Cafe. The groups—Gary Black & the Whites, the Foreign Students, Ebo, Fashion Jungle, the Mirrors, the Kopterz, the Pathetix, the Little White Squares and The Stains, to name a few.

The band I played in, The Crayons, rehearsed in the back of Ross Timberlake’s Shaker furniture shop on the corner of Pearl and Middle streets. One summer night in 1981, we upstaged a high-profile Boston band (or so our fans claimed) in the Great Northeast Music Hall (formerly The Loft, later the relocated Free Street Pub) off Marginal Way. In the wee hours after another gig, we invaded the clattering breakfast kitchen across from Whit’s End on Free Street, and I locked eyes over three rows of tables with Andrea Re, who had filtered in with her band Clouds. Fleeting fantasy.

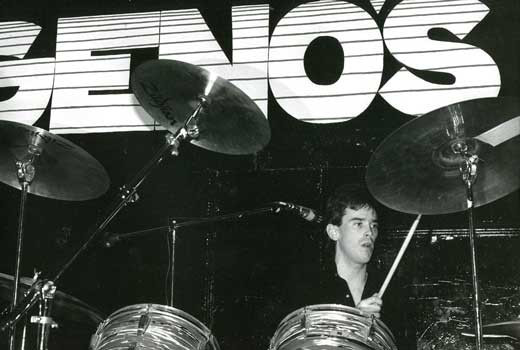

JEFFERY STANTON

Ken Reynolds of the band Fashion Jungle performs at Geno’s.

We rented PA systems from Crazy Ed’s on Congress Street. At Longfellow Square were the craftsmen of Buckdancer’s Choice. The USM-spawned pianist Chris Neville turned up to play smoking jazz.

The Face replaced the old Sweet Potato tabloid covering the music, and meanwhile a literary churn was under way. Bruce Holsapple issued the last Contraband magazine in 1980. Gary Lawless, from his Nobleboro farm, published Peter Kilgore’s love poem to Maine, The Bar Harbor Suite, in 1987, illustrated by Michael Waterman. Underground publications like Headcheese surfaced and submerged. USM students rolled out memorable issues of Portland Review of the Arts. Ken Rosen founded the Stonecoast writers workshop. Betsy Sholl’s skilled verse emerged. Fiction writers like Agnes Bushell and Alfred DePew were toiling toward well-deserved reputations. I had a memorable conversation with Rick Hautala one night at his cashier’s post in a Maine Mall bookstore.

Maybe the number of book shops in such a compact area reflected that energy. Books Etc. lasted an unusually long time on Exchange Street. Poet Deborah Ward opened artsy Anastasia’s just as Commercial Street was transforming from frame-wrecking cobblestone free-for-all to upmarket tourist trail. At the new Bookland store in a space-age contraption of a building across from Porteous, I first talked with Steve Luttrell, who in 1989 founded The Café Review, heir to Contraband. The title sprang from the No Café attached to Pat Murphy’s Yes Books on Danforth Street (where he moved from his overstuffed spot on High Street).

JOHN DUNCAN

Matt Blackwell

In the penurious winter of 1981 I sold a box of science fiction novels to Cunningham Books near Bramhall Square and haunted Carlson-Turner’s musty new digs at the foot of Munjoy Hill. Later, I picked up paperbacks at Annie’s Book Stop off Baxter Boulevard.

Artists, by then, were well-ensconced in the transition from, well, being artists to being entrepreneurs. Galleries were creating their network of New York-style reputations. Not that postwar art scenes weren’t heavily finance-sensitive all along. But after President Carter left office, the whole country got the go-ahead to regard the love of money as a virtue, and the measuring sticks of value all converted to the dollar system. If it’s dressed up expensive, it must be good.

In tucked-away corners like Bob Solotaire’s West End backyard, where poet Susan Yates dragged me in from the storm occasionally, there remained that essentially ineradicable dedication to aesthetic quality. The authenticity of ubiquitous photographer Chris Grasse. In 1985, Matt Blackwell, Scott Murray and other artists opened the NoPo Gallery—Not of the Old Port—on York Street, a labor of aggravated pushback against the moneymaking façade.

BEFORE THE GOLD RUSH

If people were unsettled by the demolition of the Libby building, they were chagrined by the real-life Monopoly game getting organized on the waterfront. “Join the Gold Rush!” one real estate firm advertised in an unabashed public display of avarice. In the Old Port, old buildings were coming down. New buildings were going up—sometimes remaining essentially empty, their cash-transfer potentials fulfilled. Upscaled!

Pouring into town to polish their social status were yuppies—hippies who had returned to the suburbs to find their back-to-the-earth inner capitalist.

Gentrification began reconfiguring Munjoy Hill, for better and worse. Peaks Island was a cool place to live—for one inconvenient winter, anyway. Even the diesel- and fish-stinking waterfront piers started turning into condos where monied yuppies could pretend to be part of dock-worker reality.

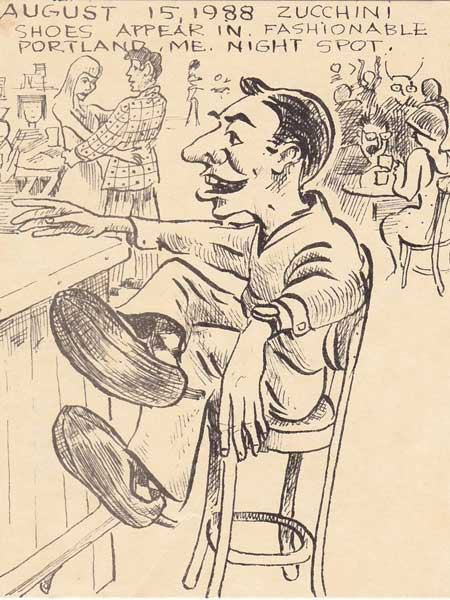

A satiric cartoon by Pete Eldredge aimed at the suddenly fashionable Old Port.

Resistance to façade-think boiled over in the mid-’80s when a project was proposed to construct condominium towers along lower Fore Street back toward the East End beach. The buildings would eliminate not only the view to the river that lower Munjoy Hill residents had enjoyed since before Longfellow was born there in 1807, but also access to the shore for anyone without the scratch to own a piece of a building. At a city council meeting called to get public input, someone stood up in the balcony seats of the council chambers and said, “This city is slipping away from us.”

A few old-time Old Port establishments endured for quite a while. One was Eli Klaman’s bottle shop, which never succumbed until long after 3-Dollar Dewey’s, nearby on Fore Street, seemed like an artifact from Old Port prehistory, which it wasn’t. Another was Zeitman’s Grocery Store on the next block from the Custom House. One night, it must have been about 1985, someone spray-painted on a wall facing up the street: “Yuppie go home to mama.” That graffiti stayed there for quite some time, as I recall.

The East End condominium project, remarkably, got shelved. But by the late ‘80s the tide was out on pre-Carbur’s Portland. Much money was there to be made, if you could afford it. Gift shops and restaurants crowded in. Many of the artists, poets and musicians of Phase 1 filtered out. NoPo shut down in 1987. In 1990, a bank foreclosed the mortgage on the Tree’s Danforth Street building.

I talked with Peter Kilgore for the last time in 1989 at a poetry reading by Robert Creeley at the Universalist Church on Congress Street. He seemed good. He was writing poems. Portlander from childhood, he soon vacated to Washington state. Two years after that, he died. By then, I was lodged in Waldo County.

These days, I don’t often get back to the home of my lost youth. But weirdly, it still takes me by surprise, when I glide silently through Congress Square, to find the Libby building gone, and see the wonderful façade.

Strange to me now are the forms I meet

when I visit the dear old town.

Dana Wilde of Troy is a columnist, editor, Fulbright scholar and former college professor. He writes the Backyard Naturalist column for the Kennebec Journal and Morning Sentinel newspapers, centralmaine.com. His new collection of writings on Maine’s natural world, Summer to Fall, is due out this summer from North Country Press.