Note: An earlier version of this story contained an error, misidentifying presidential candidate Henry Wallace.

It’s been a life marked by following his heart, even when that meant being spurned by his family.

In an era when it was not fashionable, and maybe even dangerous to do, North Haven native Lowell “Pete” Beveridge chose progressive politics and crossed stark racial lines. Beveridge told his story in his first book, Domestic Diversity (and Other Subversive Acts), and it burned bridges with family members. His political and personal choices led to a 20-year banishment from the island.

But today, at 85, Beveridge has written another book, one that explores, with pride, his ancestors, who were among North Haven’s early settlers. The Colony: Stories from a Down East Island, is a love letter to his family, he says.

And it also reveals his love of his island home.

“Although I have lived in New York City most of my life and in Brooklyn for the last 60 years, whenever I head Down East I feel like I am going home: language, food, clothing, sounds, smells, idiom, life style, architecture, attitudes—they all tell me I am home,” he said.

Beveridge spent most summers working and playing on North Haven until his early adulthood.

The Colony, published this year and available at the North Haven Historical Society, paints a complete picture of North Haven’s early history, from the Paleo Indians and Red Paint People to the early English settlers, including Beveridge’s ancestors and through the early 20th century and the close of North Haven’s agrarian chapter.

Beveridge’s grandfather, Orris Beverage (the change in spelling is explained), becomes the focal point of the book. He grew up on a working farm in the 1830s, and left the island to work as an educator and raise a family, although he returned to farm for many summers. Beveridge relatives maintain several houses in The Colony, a sprawling compound on Eastern Bay Road, the fourth spoke in the intersection of North Shore, South Shore and Middle Road, though many have been sold recently.

Domestic Diversity, although written first, follows Pete Beveridge off the island in the 1940s and ’50s. Beveridge wrote Domestic Diversity (and Other Subversive Acts) to “record and expose the impact of racism on our family’s little corner of society,” he said.

Beveridge’s political awakening began as he took his first summer job in manual labor, a short-lived stint packing sardines in Rockland. Paired with his increasing awareness of racial tensions in his native New York, Beveridge’s experiences led him to defy the school culture at conservative Horace Mann by openly supporting Henry Wallace’s presidential candidacy for the Progressive Party. After marching as a Young Progressive with Pete Seeger, Beveridge spent a summer on North Haven working at Alton “Tonny” Calderwood’s farm.

PERSONAL POLITICS

Beveridge’s politics came to define his relationship with his family and inevitably with North Haven.

As a student at Harvard, Beveridge became a member of the campus Communist Club and served as president of the Young Progressives of Harvard. He campaigned enthusiastically for racial equality and against the ROTC’s required loyalty oath. As he discovered while writing Domestic Diversity, his activism caught the attention of the FBI, which maintained an extensive file on him.

He dated Dorothy Silberman, a young Jewish Radcliffe student whom Beveridge brought to North Haven. After one such visit, his mother wrote to urge him to reconsider his relationship with her, although she denied any anti-Semitism. Silberman and Beveridge’s relationship didn’t withstand his move to New York to attend graduate school at Columbia, but Beveridge said his mothers’ response to his Jewish girlfriend foreshadowed his family’s reaction to his African-American wife.

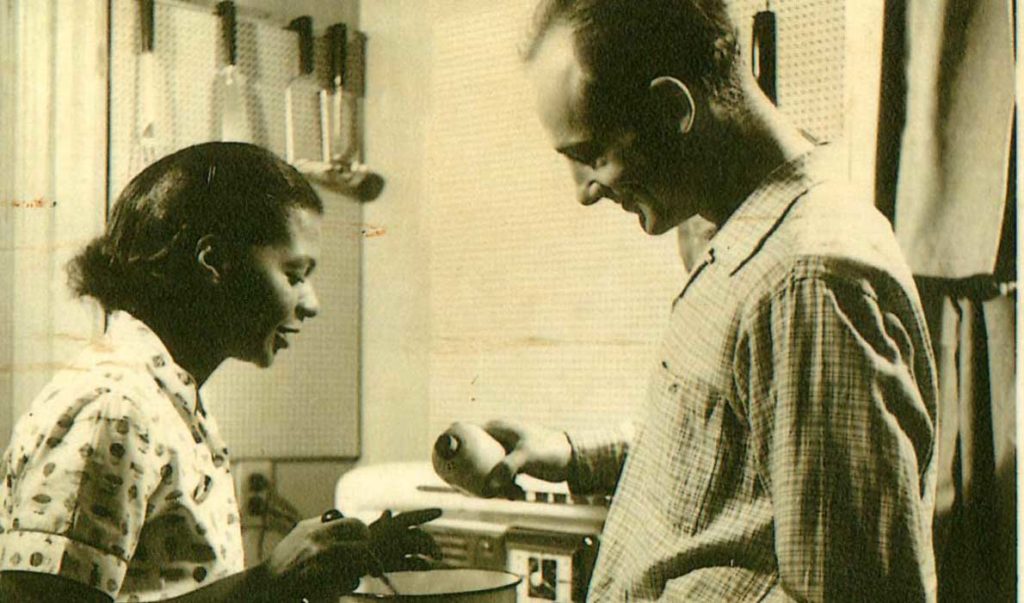

Beveridge met his future wife, Hortense “Tee” Sie, at a fundraiser she was hosting for a film she had edited highlighting the onset of apartheid in South Africa. Both Communist Party members, their relationship blossomed during commutes to Washington, D. C. to protest against the execution of the Rosenbergs for espionage. When marriage became inevitable, Beveridge hoped to bring Tee to visit with his family on North Haven, but was rebuffed. In a letter to his parents in 1953, he compared the island to a “Jim Crow restaurant,” he remembered.

“In the old days in small rural towns like North Haven everyone was dependent on neighbors. Mutual trust and support was all-important. Any outsider had to earn that trust,” Beveridge said. “If your grandparents were born there, you could be trusted; all others were suspect.

“I don’t think North Haven was unique in this respect although the fact that it was literally an island may have made it more insular than its mainland counterparts,” he said.

The suspicion of outsiders extended, at various times, to Catholics, Jews and summer visitors from New York, in addition to Tee.

Beveridge’s 1953 marriage to Tee marked the beginning of his 20-year exile from North Haven. During that time he began working as a house painter, and later as an interior designer for commercial institutions. He remained politically active. Despite his family’s fears that he and Tee would have a biracial child, they were unable to conceive and instead adopted their son Jesse.

In the 1970s, Beveridge’s Uncle Eliot invited his family to North Haven.

“To Eliot’s credit, 20 years later he broke my long exile from the island by inviting me and Tee and my son Jesse to stay with him for a week at the farm house,” he said.

In 1983, Tee and Pete separated, in large part due to his newfound sobriety and her continuing struggle with alcohol addiction, he said. She died in 1993.

At 62, Beveridge retired from the design business. He later married artist Caro Heller.

“Caro and I ran a volunteer people-finding service for many years, mostly helping to reunite people and families separated by adoption. We successfully solved about 80 cases,” he said. Beveridge’s son Jesse was their first case, and when they successfully located his parents and a previously unknown sister, their interest was sparked.

Heller died in 2014. At 85, Pete Beveridge cooks, stays active in community politics, makes cabinets and furniture in his woodworking shop, and is still telling his family’s story.

“I guess in the back of my mind was the hope that this second book, which is sort of a love letter to the family, might make up for bad feelings generated by my first book,” he said. Beveridge said he wrote The Colony as a way of preserving the “non-physical part” of his family’s heritage in the face of many of their historic homesteads being sold outside of the family.

“For the past 30 years I have always stayed at the farmhouse where my grandfather was raised which was owned by my uncle Eliot and inherited by my cousin Charles. That has now been sold. If and when I visit again it will have to be as the guest of one of my cousins who still own a cottage in the Colony,” he said.

For now, Pete Beveridge stays in touch with the island he considers home by reading the North Haven News. Among his extended family, he’s the only one with a connection to the island.

“In fact, we are a very diverse group with ancestors from the five major continents,” he said. Beveridge’s wide world view puts North Haven in perspective in both of his books.