A friend of mine once wrote that fishing villages came in to existence once they began to disappear. Once seaside villages were lost to other forms of development, nostalgia over their loss emerged, giving rise to the term “fishing villages” in the early 19th century.

Most of the time, it is hard to see what we are losing; a subtle behavior, use of language, or set of ethical commitments, slowly replaced by something else. It only becomes clear once we can see it in the rear view mirror. Other times, the transition is sudden and apparent, when an access point to the ocean is closed off.

At what point do we lose something that is fundamental to our sense of community, and recognize this loss as a fundamental threat to the future of the place we care about?

Changes in how we behave toward one other may forecast an unraveling of the social fabric that makes a community unique and valued. For example, the loss of the common mannerism of waving to neighbors while driving would be viewed as tragic in a number of the communities along the coast.

While seemingly insignificant to the untrained eye, an entire hierarchy of waves clarifies your relative position in the community. A single finger lifted off the wheel, two fingers, a full lifting of the hand… all send a message of knowing one another, mutual respect and being a part of the community. Lack of interest in pulling together a parade might be a more overt example of changes to behavior.

The sale or loss of key community spaces can be a sign of a community at risk of losing itself. Perhaps we are most aware of it when a commercial fishing wharf or boat building facility is converted from commercial to recreational uses. Housing tends to become a part of community discussion when the children of year-round residents can no longer afford to buy homes in the communities where they grew up (See the story on North Haven housing in this issue).

The issues are far from isolated to the islands. I recently attended community discussions in St. George about the need for workforce housing. The town of St. George (Port Clyde, Martinsville and Tenants Harbor) is the second least affordable municipality in Knox County, behind North Haven island.

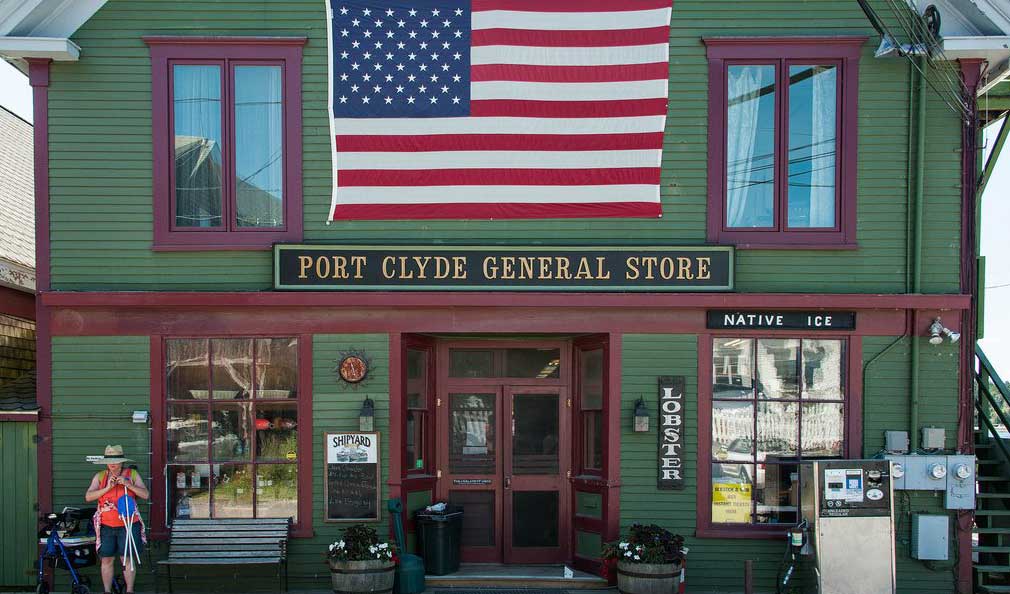

I would argue that a far less obvious threat to a community occurs each time that a general store is put up for sale. Many general stores are on the waterfront, near the ferry or the center of town. In fact, the future of all three St. George general stores are in question. As with housing, the islands are a decade or more ahead of St. George when it comes to addressing the need for workforce housing, and the future of key community properties like general stores.

Stores are often locations where people gather early to share a cup of coffee, stories and information and to spread misinformation. They play a critical role in maintaining the social fabric of a place. When they close seasonally or sell and close, a community loses an important meeting place.

Beneath the loss of general stores, commercial fishing waterfronts and affordable workforce housing is one single issue: Real estate in these increasingly desirable places does not follow the basic economic principle of supply and demand. More demand drives up prices without creating more supply, and before long, key pieces of community infrastructure become unaffordable to those earning wages in the local economy.

How do we avoid being defined by a sense of nostalgia for what once was? Today, many people are working hard to hold onto our working waterfront communities, knowing all the while that they are changing. Each shift in behavior, each time a key community property goes up for sale, we have an opportunity to come together and think and act creatively to hold on to the things that make our communities remarkable places to live.

Rob Snyder is president of the Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront. Follow Rob on Twitter @ProOutsider.