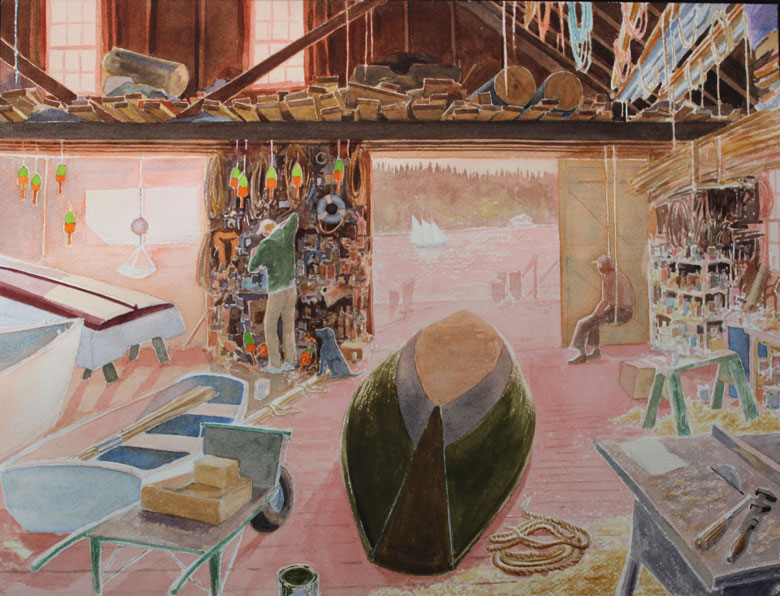

“My paintings generally celebrate local culture and traditions,” which in this setting are embodied by wooden boatbuilding at the J. O. Brown Boatyard, writes painter Seaver Leslie of his watercolor of the interior of the North Haven Island landmark.

Describing his painting, Leslie starts with the shop doors, which were “letting in beautiful light.”

The man on the swing to the right is Stanley “Toot” Waterman, part of the island’s Waterman clan, while at center, his back turned, stands Foy Brown, Thorofare harbormaster and co-owner of the boatyard founded in 1888 by his great-great grandfather James Osmond Brown.

The flipped-over dory belonged to Foy’s brother, Jim Brown, who used it for duck hunting. Out the open door, sailing by, is the late Capt. Mark McClellan’s schooner, Simplicity.

“The texture and spirit evident there; the materials; the design of the vessels; the tools that have been handled by the boatbuilders’ forebears…”

Leslie painted at the boatyard in the spring and summer of 2009 and 2010, focusing on the interior, with a series of detailed drawings preceding the watercolors.

“I like to sketch things out to organize the structure of the picture and to begin to understand the light,” he explains. Such studies were especially necessary to build such a complex image.

While visiting the boatyard, Leslie felt a deep sense of camaraderie among “craftsmen bound by both pride and humility.”

He appreciated how friendly Foy and his crew were, even as they concentrated on their tasks.

“There was a good word for everyone who stopped by,” he recalls.

Leslie waxes lyric about the family-owned business that has built lobster boats, launches, and sailing vessels for going on 140 years.

“The texture and spirit evident there; the materials; the design of the vessels; the tools that have been handled by the boatbuilders’ forebears and passed, with their knowledge, to the next generation—all of this counts in making a well-functioning and beautiful wooden boat by hand.”

These crafts, the painter further notes, are “archetypal designs that have existed on Maine waters for centuries.” That fact puts the boats and their builders “in harmony with the past and the present, land and sea.”

The Boston-born Leslie first visited North Haven when he was 13 and crewing on the schooner Alida. He remembers mooring in the Thorofare and taking on fuel and provisions from Brown’s Boatyard. Later, as a young man, he returned to the island to see his friend and fellow painter Eric Hopkins.

He has also had occasion to visit architect Toshiko Mori and her husband, sculptor-architect James Carpenter (Hopkins’s mother, June, encouraged the couple to buy the old Cushing Thomas farm in 1984).

Leslie’s CV includes teaching appointments and artist residencies at the Rhode Island School of Design (where he earned BFA and Master of Education degrees), Parsons, Wellesley, and the University of California, San Diego.

A classmate of famed glass artist Dale Chihuly at RISD, the two collaborated on “Ulysses Cylinders,” inspired by James Joyce’s novel. Leslie is also known for his allegorical paintings, which critic Edgar Allen Beem once described as “unqualified” indictments of “modern America for crimes against the earth and her people.”

Leslie also founded Americans for Customary Weight and Measure, an organization that called for an end to the metric system in the U.S. in the early 1990s.

“Good old Yankee common sense beat down the effort of these people trying to make a buck from simply changing over from one measurement system to another,” he told a Christian Science Monitor reporter at the time.

A longtime resident of Wiscasset—family ties go back more than a century—Leslie helped spearhead a campaign in 1995 to create the Morris Farm Trust, preserving one of the last working farms in the area. The trust promotes sustainable agriculture and stewardship through education and community involvement, while enhancing food security in the midcoast.

In light of the recent heroic efforts to save and restore the J. O. Brown Boatyard during and after the January storms, Leslie reflected on what the place means to North Haven islanders: “It’s the hub of the island—the absolute center of its traditional culture and daily life,” he writes. “It’s the omphalos stone—one of the last bastions of Maine’s great craftsmanship tradition.”

Leslie also considers the boatyard to be the bulwark against what he calls “the oncoming tide of senseless, short-sighted ‘progress’” and “an important beacon for young people, showing how beautiful, useful things can be crafted in the old way, with care and purpose.”

His brilliant watercolor is a testament to his passion for this special place.

Carl Little’s latest book, co-authored by his brother David, is The Art of Penobscot Bay (Islandport Press).