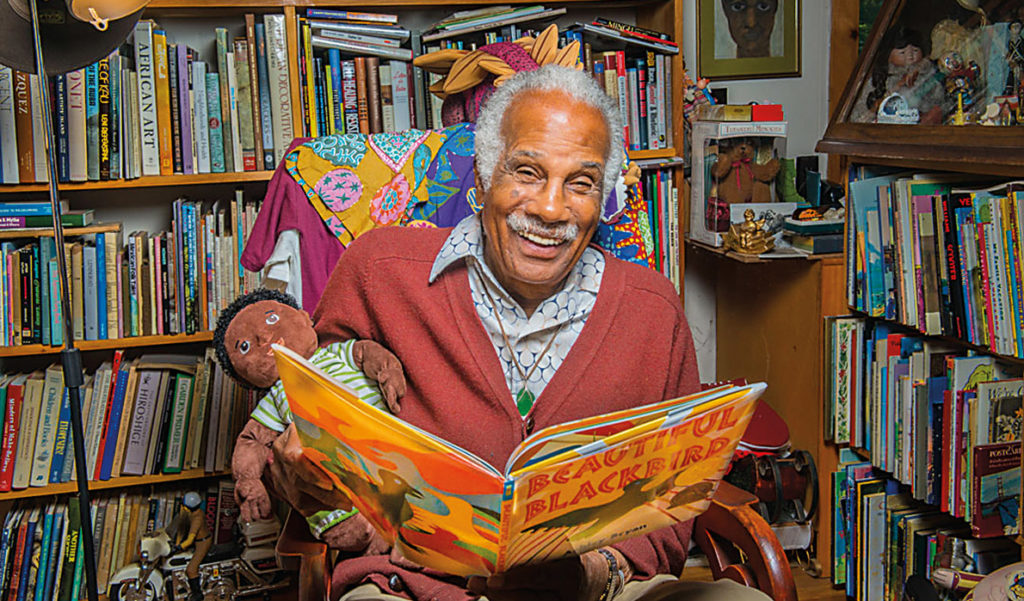

The first time I visited Ashley Bryan’s home on Little Cranberry Island, also known as Islesford, I knew I’d met an extraordinarily special person. I still feel that way every time Ashley and I meet.

When asked to describe it at the time, I said it was like walking into a house where someone’s emotions and intellect were completely visible. It is an experience that is at once shocking, a little confusing, but ultimately inspiring. Ashley was generous, passionate, humble and embracing, all of which left a powerful impression on me. I left his home a changed person.

Today, I serve on the boards of several nonprofits, among them the Ashley Bryan Center. This organization is based on Islesford and in Cambridge, Mass. It is dedicated to preserving, sharing, and celebrating Ashley Bryan’s life and work as an artist.

I am on the board because I know a bit about organizing nonprofit resources. I also serve because on a foggy day in August many years ago, Ashley took my daughter and a friend’s family into his home and gave our children lessons in creating papier-mâché stained glass windows. He was so kind and generous, and he opened my daughter’s eyes to a new world.

That day, my daughter learned that when Ashley makes a mistake when writing or drawing, he doesn’t start over. He turns the mistake into a flower and then continues what he is doing. She does the same now.

This sort of playful approach to moving forward in life despite mistakes is very much a part of what makes Ashley so remarkable.

I serve on the center’s board with Ashley’s friends and family, island neighbors who have known him for many decades, and those who have come to know and love his work.

The head of the Ashley Bryan Center, the very talented Nick Clark, was the founding director of the Eric Carle Museum, which celebrates children’s literature and is inspired by the work of the author of The Hungry Caterpillar and other books known by parents around the world.

Each time I head to a board meeting, I ask myself, “What am I doing?” I don’t know anything about African-American art or literature. I’m not a person of color. I’m not a particularly knowledgeable historian of the period or places in which Ashley has lived and worked.

But Ashley has lived—and continues to live, into his 90s—an extraordinary life. As a black man on a largely white coast, and as an artist, not a fisherman, he became a central part of his island community. He set an example for me to strive to put myself in interesting and surprising situations. After all, he became part of a community where he couldn’t have been more different.

On the board, we grapple with the future of Ashley’s many books. How do we make sure that they continue to inspire young people of color and teach tolerance to the rest?

We’ve built a retreat center on the island where people can meditate on some of Ashley’s most beautiful works and find the same peace and connectedness to people and place that he finds in the island experience.

Ashley has been nothing if not prolific and generous. We work to get our arms around the extent of his genius and productivity, knowing that he has gifted so very much art to people around the world. And yet we must ask ourselves, what is the ultimate role for our organization? Are we here to make all of Ashley’s works available to world?

The answer, of course, is yes.

As the board member who knows the least about much of this, I find myself in the front of the room facilitating the discussion among people whose knowledge and passions run very deep. The guy who knows the least—me— ends up at the front of the room. Perhaps this is a life lesson to consider on another day.

I’ve found this kind of public service to be a learning experience, but also a way to share what I know. Budget management, governance, the struggles of staying focused, and fundraising—in my work at the Island Institute, I’ve grown through experience in each of these facets of nonprofit work.

Our coast has a thriving non-profit community which requires volunteer support to get the work done. Whether serving on the front lines or in board meetings, the rewards are the same—being part of a larger effort to improve life here, and joining with people who share a passion to do the same.

Ashley Bryan’s passion is his art. And just as he works through his missteps on canvas or on paper, knowing the final work will bring delight to those who see it, our volunteer labor—whether we are suited to the work or not—produces a world that is—we hope—a little bit better.

Rob Snyder is president of the Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront. Follow Rob on Twitter @ProOutsider