Calm Command: U.S. Chief Justice Melville Fuller in His Times, 1888-1910

By Douglas Rooks; Maine Authors Publishing (2024)

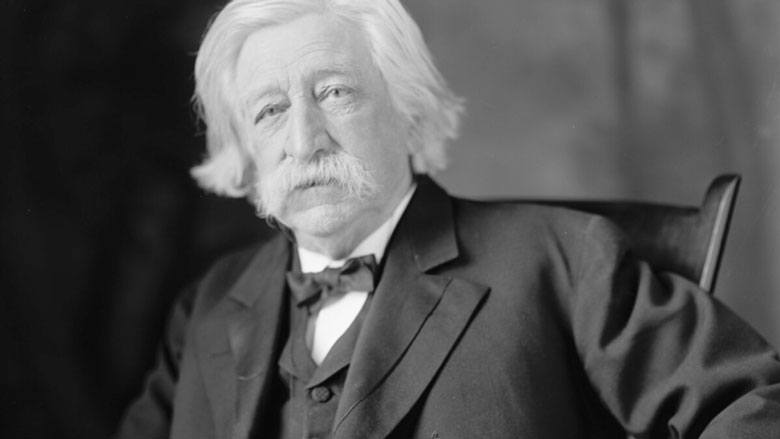

In February 2022, a statue of Melville Fuller, the Augusta native who served as chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1888-1910, was quietly removed from its spot on the grounds of the Kennebec County Courthouse where it had stood for nearly nine years.

Everyone who’d been paying attention knew what this was about.

Fuller presided over the court in 1896 when the now infamous Plessy v. Ferguson case was decided. He voted with the 7-1 majority ruling against the claim by Homer Plessy, a black man who could nonetheless pass for white, that he should have been allowed to use a railroad car designated for white people. The ruling upheld the practice of separate but equal facilities for different races of people.

One hundred twenty-eight years and the overruling of the separate but equal principle in Brown v. Board of Education in 1955, we think we have a pretty clear picture of right and wrong in America’s sorry, bloody racial history. Fuller voted to uphold a principle that would underpin oppressive Jim Crow laws for decades. Shame on him. His statue must come down.

We learn in Douglas Rooks’ new book about Fuller’s life, Calm Command, that reality is nowhere near so simple.

Fuller was born in Augusta in 1833 and participated, like others in his family, in Maine politics. He moved to Chicago in his 20s, established a successful law practice, and became an important figure in Illinois politics. Although a Democrat, he supported Lincoln’s position in the election of 1860, which was not to end the practice of slavery, but to limit its expansion into Western states.

In keeping with that aim, Fuller backed the effort through the Civil War to keep the union together but, like many at the time, thought the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 was a political mistake.

Rooks details how Fuller’s integrity, universally praised good nature, and keen knowledge of law won him many allies in Washington. In 1888, President Grover Cleveland persuaded him to fill the vacancy for chief justice of the Supreme Court.

“Brown’s bland assurance that there was something natural about racial prejudice offends us today but was widely accepted then.”

Fuller did not write the majority opinion in the Plessy case, which at the time, Rooks explains, was not considered to be of much consequence. Several similar cases had been decided along those lines.

Justice Henry Billings Brown spelled out the persuading issues for the majority in the 7-1 decision (one justice was absent for the case). While agreeing that the Constitution and the laws following from it grant the government oversight of civil and political rights, Brown wrote, trying to legislate social rights would be extremely problematic.

Separate but equal accommodations for the races seemed fair to the justices as well as many, if not most people who opposed slavery following the Civil War. As expressed in the Plessy opinion, Rooks says, “Brown’s bland assurance that there was something natural about racial prejudice, or that one race could be ‘inferior,’ offends us today but was widely accepted then.”

Here in the 21st century, we know that the conclusions in Plessy were used to underpin Jim Crow laws, but the justices had no way of knowing that in 1896. Deference to states’ rights arguments on social issues seemed the more hopeful course. Rooks quotes Supreme Court Justice David Souter in 2010 reflecting that “members of the court in Plessy remembered the day when human slavery was the law of the land. To that generation, the formal equality of an identical railroad car meant progress.”

Rooks’ clearly written, meticulously researched book gives the background of Fuller’s life and of the Plessy case, and also the historical backdrop of the Constitution and the political and social machineries of the 19th century, in tandem with discussions of cases in constitutional, labor, and maritime law.

A point that returns again and again is that Fuller was viewed as an extraordinarily capable administrator who shepherded the federal court system through a major, necessary overhaul and expansion. There are reasons why we may want to remember Fuller favorably, despite a serious mistake rooted in the ethos of his time rather than the individual himself.

Calm Command is a careful, well-written book that throws light on not only Melville Fuller, but the boiling history he helped guide the U.S. through, for better and worse.

Dana Wilde is a former newspaper editor and college professor. He lives in Waldo County.