By Catherine Schmitt

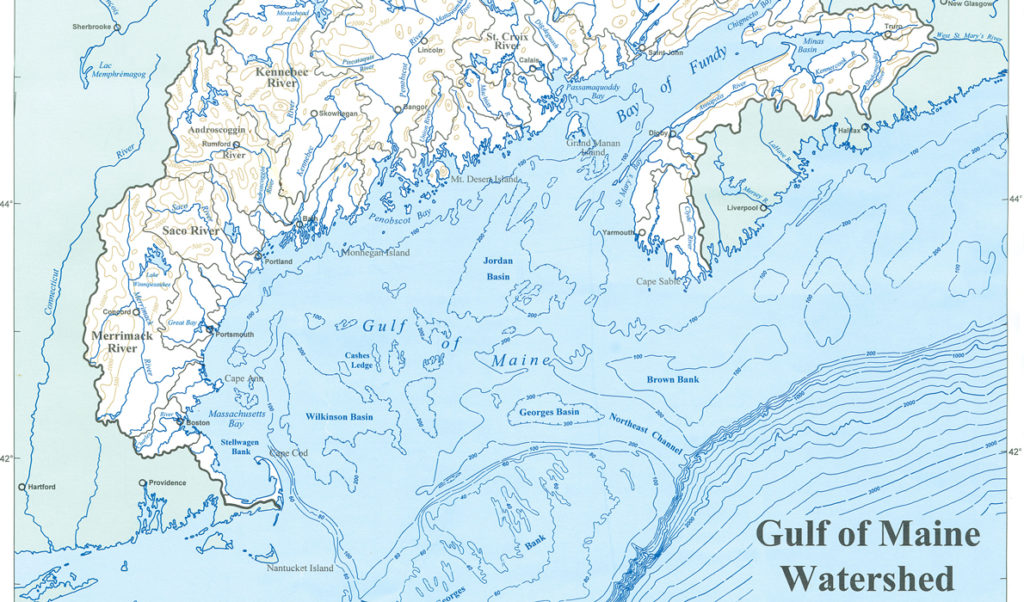

Animated maps show currents flowing in, around, and out of the Gulf of Maine, this sea within a sea, a counterclockwise gyre from the edge of vanishing Arctic ice, in and around to the clenched fist of Cape Cod, and then out.

As the currents churn like underwater rivers, the tides rise and fall, flooding and draining the shoreline, today and today again: flood and drain, flood and drain. Speed up the maps and the tides are like a heartbeat, the currents arteries connecting this sea with the sea beyond, where more currents spiral off the continents.

“The ocean is the climate’s heart and circulatory system. Warming is a stress on the heart,” Aimee Bonnanno of the New England Aquarium told a crowd of 345 people, mostly scientists, who had gathered to try to understand the future of the Gulf of Maine in a hotter climate. She urged them to communicate what they know with language and metaphor.

Bonnanno was one of many presenters at the Gulf of Maine 2050 International Symposium hosted by the Gulf of Maine Council on the Marine Environment and the Gulf of Maine Research Institute in Portland in November. Organizers structured the week-long meeting around three main forces of change: sea level rise, ocean acidification, and temperature, with a full day of presentations and discussions devoted to each. Teams of scientists also worked in the months leading up to the meeting to draft background papers, including new, higher resolution analyses by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and Canada Department of Fisheries and Oceans, using existing climate models, scaled down to the Gulf of Maine region.

“The Gulf of Maine has never been hotter than it has in the last decade,” said Michelle Staudinger of the Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center, summarizing the results of the temperature analyses.

The modeling predicts a 2050 Gulf of Maine surface temperature that is warmer than the 1976-2005 average by one to four degrees Fahrenheit. The results for future salinity are more uncertain, but most outcomes show a freshening as a result of Arctic melting, and altered circulation. “All models show warming, and more stratification,” said Andrew Pershing, chief scientific officer of the Gulf of Maine Research Institute and lead author of the temperature study. If greenhouse gas emissions are slowed drastically, the future could be similar to the Gulf of Maine of the late 1990s-2000s. With continued emissions, 2012 will seem like a cold year.

Summer flounder, scup, black sea bass, longfin squid, and Jonah crab like it warm. Gone with the cold are cod, pollock, herring, cusk, and Northern shrimp.

Kelp forests have collapsed in southern Maine due to warmer water, reported Douglas Rasher of the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences.

“The species that are declining are leaving gaps in the roles they play in the ecosystem. How are those gaps being filled?” said Staudinger.

Some animals, like Northern right whales, are still using the Gulf of Maine, but for less time, or are following their food sources to new areas. Zack Klyver had to lengthen Bar Harbor Whale Watch trips from three hours to five hours to be able to get to the whales off Grand Manan.

Other animals have altered their own life cycles, like puffins laying eggs later.

But a shared vision of the Gulf of Maine in the year 2050 proved elusive.

For example, “sea level rise” appeared to mean different things to different people. There was no consensus on a single number for how high to expect the sea to be in 2050 (how fast will the West Antarctic Ice Sheet melt?) Rise rates are complicated by an increasing volume of water from melting glaciers, storm surge, and swollen rivers. Shallow areas flood, while along the steep, rocky coast, currents become faster as more water moves through the same narrow channels. The Eastern and Western Maine Coastal Currents, circulatory systems in the Gulf, are also projected to speed up.

Some connections were made, however, across ideas and regions, which Pershing was excited to see.

“For example, that the recent warming in the Gulf of Maine has likely masked effects of ocean acidification,” he said. “If we get a cool period, will that mean we suddenly have to deal with effects of changed ocean chemistry?”

The sense of urgency was too great, and the urge to act too strong, to dwell only on the negative.

“We’re scientists. We should be suggesting solutions, not just what’s wrong with climate change,” said Gail Chmura of McGill University, who described efforts to store carbon in marsh lands, breach dykes, and realign landscapes.

Though scientists are ready to talk about the changes they are documenting, they have to learn how to talk to each other better and how to listen, according to Hattie Train, a graduate student at the University of Maine.

“They’re all talking about the same issue and they think they’re having the same conversation, but they’re not.”

Train and others at the symposium called for improved communication.

According to Peter Wells of Dalhousie University, who analyzed Gulf of Maine communications, lack of awareness of new information remains a major barrier to its effective use in managing the coast and ocean. He found that critical data on indicators of ocean health may be ignored—perhaps for the same reasons we ignore a pain in the chest. The consequences are too awful to imagine, even 30 years from now.