This story first appeared in National Fisherman and is reprinted here with permission and gratitude.

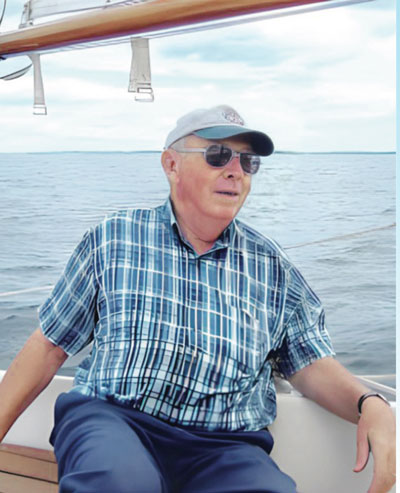

Francis J. O’Hara Sr., president of the O’Hara Corporation, passed away on Aug. 3 at his home in Camden at the age of 91. If there is a name that’s synonymous with Maine’s fishing industry, it’s Frank O’Hara.

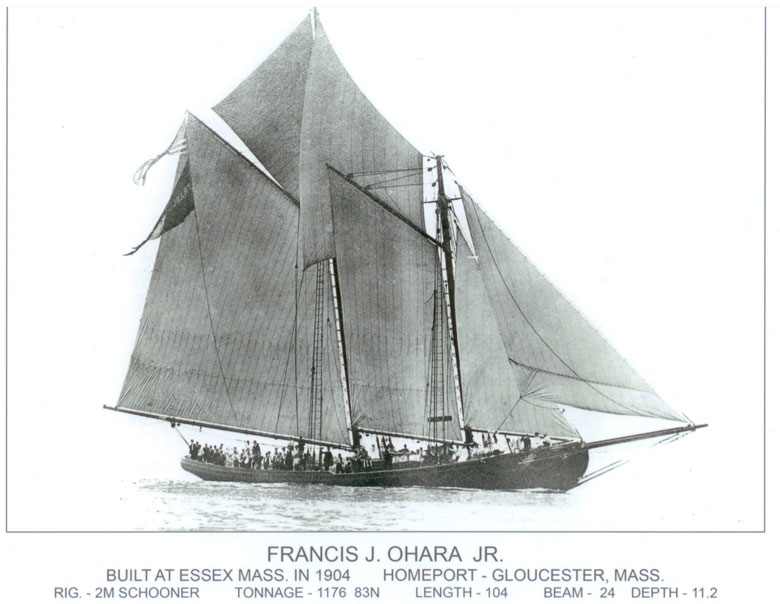

The O’Haras started building boats and developing a vertically integrated seafood company in the early 20th century. The family’s first boat, the F/V Francis J. O’Hara Jr., was built in 1904 and sunk by a German U-boat during World War I.

Gradually, the O’Haras moved from T-Wharf in Boston to Portland, Rockland, and Lubec. Over the century, the O’Hara Corporation increased its footprint to include New Bedford, Mass.; Seattle, Washington; Dutch Harbor, Alaska; and Zhuange, China. The company headquarters remains in Rockland.

From the age of sail and sextants to the age of 3,500-horsepower engines and satellite communications, the O’Hara family has defined and been defined by the commercial fishing industry.

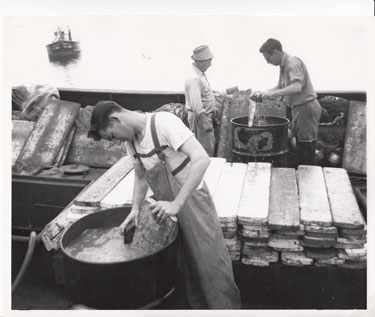

Born in 1932 in Boston, Frank O’Hara began working for his father’s company in Rockland at a young age. In those years the O’Hara vessels, including four 85-foot trawlers, caught and processed millions of pounds of redfish, breaking records for landings. The company froze much of that fish to feed U.S. troops during World War II.

From their company’s beginnings, the O’Haras had a knack for making the right moves, understanding a business intrinsically connected to an unpredictable resource—wild fish.

Frank Sr. worked with his brother on the docks through school. After a stint at Boston College, he found his life-long mate, Jill, and they married and began their life together. Frank took the helm of the company in 1955.

At that time, Maine fishermen followed redfish past Newfoundland, and occasionally, all the way to the Labrador Sea.

The O’Hara fleet operated out of Rockland and consisted of several side trawlers, all named after family members. It was not long before a change in fish stocks required the fleet to switch from ocean perch (redfish) to groundfish including haddock, cod, pollock, and flatfish.

After the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act established the 200-mile limit in 1977, a change in the fishery required a different style of boat, which began the shift to stern trawlers that were built from 1979 to 1984. The O’Hara’s Araho was one of the first stern trawlers with a steerable nozzle or rudder which increased horsepower and made steering more efficient.

Frank was also one of the first to install a processing room below deck to allow crew to head and gut the fish in better conditions, along with an automated gutting machine designed in Nova Scotia. Frank built four sister ships to the Araho—the Freedom, Ranger, Enterprise, and Defender, all named after America’s Cup winners.

By establishing its operations in Rockland, F.J. O’Hara and Sons gained an advantage of being closer to the rich resources of the northern edge and northeast peak of Georges Bank, but when Canada asserted control over some of those grounds, the O’Hara fleet lost access.

“We suffered for three or four years after that,” said Frank Jr. Frank Sr. sent bigger boats to the tail of the Grand Banks, in international waters. It took nearly a week steaming for the boats to get there, then they fished like mad for five or six days, and then steamed home loaded with flounder.

The lack of access eventually led the O’Haras to change the course.

“We purchased an abandoned oil supply vessel and converted it to a factory processor, the Constellation, thinking we’d do squid, mackerel, and butterfish. But that didn’t work out as we hoped. It was getting hard fishing on the East Coast. The factory in Rockland was closing down due to the lack of fish. We decided to look west and with the help from Sewall Maddocks, who ventured to Alaska and came back and said there’s some fish out there, a decision had to be made,” Frank Jr. remembered.

“We took the Constellation out first, headed for the Panama Canal. Just outside Jamaica, we blew one of the main engines. I can remember my father saying, ‘This is crazy. We should have never done it,’” Frank Jr. said. “But after 1990 we were established in Alaska and then we focused on getting more boats out there.”

Since the move to Alaska, the O’Hara operation in Rockland shifted to catching and selling herring for lobster bait and catering to both lobster boats and pleasure craft as a marina.

Frank Sr. was connected to Connors Brothers of Black’s Harbor, Nova Scotia, the largest sardine producer on the East Coast. Connors Brothers were not allowed to own U.S. fishing boats, so the O’Haras purchased the Atlantic Mariner and converted it to a seiner/pair trawler to fish for herring and mackerel.

“Soon after, we became partners with long-time herring fisherman, Alfred Osgood of Vinalhaven. This put us on the map and in a great position to supply the coast of Maine lobstermen with a chilled, salted product to be used for catching lobster,” Frank Jr. said.

Frank Sr. was a driven man who put the crews of the boats, and the employees of the business first. “He always said the people do not work for us, they work with us,” says Frank Jr.

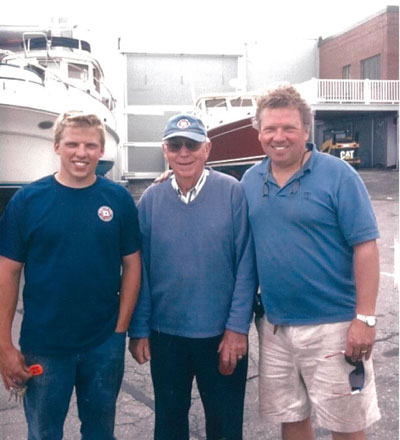

“He went to his office every day until he was in his early 80s,” adds Frank Sr.’s grandson Frank III. “He was always there when I was young. He taught me how to drive a truck, operate a forklift, and pick up trash around the marina,” he said.

“As he got older, he was less focused on the business and more focused on the family,” says Frank Jr.

Frank Sr. took the reins of the company and pushed it, even if reluctantly at times, into new territory. His death leaves a big hole in the fishing industry, but he has left a legacy to fill it. The O’Hara Corporation has provided careers not only for his children and grandchildren, but the next generation as well.