It’s a foggy and rainy May. A little chilly. Today is a good day to talk about ocean temperatures.

Across most of the North Atlantic, sea surface temperatures have been absolutely shattering records recently. Yet when we look at the buoys in the Gulf of Maine, this winter and spring have been remarkably… average.

The surface temperature today (May 1 as I write) at the Penobscot Bay buoy is about 46 °F. That’s warmer than the 20-year average for May 1 (44 °F) but shy of the highest recorded for this date (47.68 °F, recorded in 2013).

When the major ocean heatwave that struck the Gulf of Maine, many of us in Maine were scrambling to understand what it meant…

If you check out the other buoys around the Gulf of Maine, you’ll see a similar pattern—surface temperatures running a hair above average through the winter and spring with some ups and downs, while some locations are even a little below average.

Twelve years ago, when the news was abuzz with the major ocean heatwave that struck the Gulf of Maine, many of us in Maine were scrambling to understand what it meant for lobsters, whales, cod, puffins, and people.

Maine was one of the first places to get an ocean climate shock like that. Much has been written about that heat wave, but one of the take-home lessons for me as an oceanographer was that, if we had been watching the deep-water temperatures (600 feet or so), we would have seen the heatwave coming a year or two earlier. When big changes happen down there, they eventually overwhelm what happens at the surface.

So, as I’ve been perusing the buoy data, I decided to look deeper. The great thing about the NERACOOS buoys is that you can get up-to-date data all the way to the bottom of the Gulf of Maine.

So what’s going on down there, anyway?

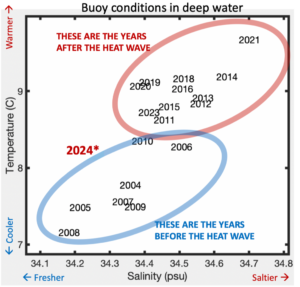

To cut to the chase, the deep-water masses are colder and fresher than they’ve been in more than a decade. The pattern has been strengthening over the past few months. For an oceanographer, this suggests a shift in the Gulf’s primary water supply away from the warmer, saltier subtropics to the colder, fresher subarctic.

It’s hard to say how long this pattern will hold, but it has lasted long enough to catch my attention. We haven’t seen anything like this since before the 2012 heatwave.

If it does hold, we should keep an eye out this summer for the same biological patterns we saw before the heatwave. When deep waters are cold and fresh, it affects things like the timing of lobster molts, the production of forage fish, and the supply of food for North Atlantic right whales in eastern Maine.

Before the heat wave, shellfish closures were longer and more common. And I’ve been hearing from neighbors recently that the alewife timing is off. We’ll be checking in on these and other conditions. Stay tuned, and keep an eye on those buoys.

Nick Record is a senior research scientist at Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in East Boothbay.