Sunrise and the Real World

By Martha Tod Dudman (2023: Islandport Press)

More than once, Martha Tod Dudman’s Sunrise and the Real World sent me back to its earlier passages and had me asking, “Really?” and “What the…?”

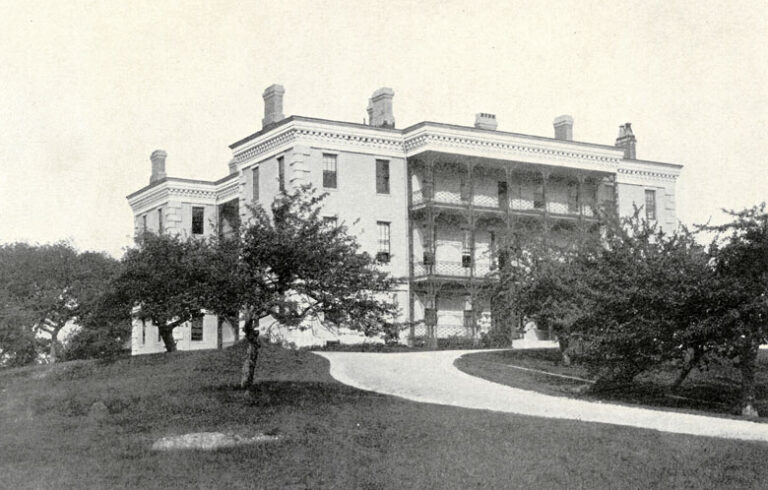

Lorraine, the novel’s narrator, recounts her time while in her early 20s working at a residential therapeutic school near Northeast Harbor. In the 1970s and 1980s programs like the novel’s “Sunrise” often served to corral teens with nowhere else to go. Even with no training and no discernible qualifications, Lorraine’s hiring would not have been an anomaly.

Some of the teens come from homes where parents were overwhelmed by the behaviors and could afford the tuition. But most were “state wards,” as Dudman calls them, children for whom the state holds custody. Rather than living in foster care, these teens are one step away from jail or hospitalization.

As described, Sunrise doesn’t seem to house those with addiction or on psychiatric medications; at least those problems and possible treatments aren’t mentioned. Sunrise does have children with histories of abuse and neglect, and angry, impulsive, aggressive behaviors. The Sunrise approach is common to “wilderness” programs, using time outdoors to give students a different setting, stimulation, and distraction, and ideally providing a sense of accomplishment in meeting challenges.

Her general anxiety is palpable; Lorraine seems naive and immature.

That programs and problems like that exist (hopefully now better regulated and staffed) didn’t prompt my questions. I struggled with Lorraine’s cluelessness and lack of self-preservation. She stays in compromising situations, tinged with real harm. Things that didn’t worry her should have.

It made me wonder if she were comfortable with risk and danger, as if she’d already been exposed it and it was “normalized.” She offers clues to that possiblity when she refers to a past abusive partner but avoids sharing family or childhood details.

Lorraine likes the natural beauty of the Acadia area but the school job seems primarily about the paycheck. Chaperoning kids is something she is able to do, like babysitting.

Her future seems mostly oriented to finding a husband, and as the book begins, there is a nice young man she has started to get to know.

Her general anxiety is palpable, and she seems naïve, immature, and judgy, sizing up people up based on appearance. Tall is great, thin is excellent. Clothing, shoes, and hair styles are treated as a reliable measures. It seems Lorraine’s rigidity in standards might be a way to feel more secure; she never realizes the superficiality it rests on.

What Lorraine needs is kind support, someone mentoring her, giving her helpful feedback. But only if she would be able to trust that someone was trying to help her.

Aside from a few friendly staff, Lorraine feels thrown to the wolves, a way she referred to students but could have applied to at least one adult—Elliott, the almost psychologist. Instead, she flirts with Elliott and sleeps with him at work, knowing he has seduced other women on staff.

There are other vulnerable roles she accepts, like being lifeguard on the lakefront without any rescue skills, and chauffeuring groups of students on trips in unpopulated areas with no staff support (or cell phones).

That institutional irresponsibility certainly isn’t Lorraine’s fault. Ironically, the very setting of this book—Sunrise as a place where children are denied choices and freedoms—is where the adults would clearly benefit by having better boundaries.

As workers complaining about chaos sometimes lament, “Monkeys are running the zoo.”

Lorraine survives the job long enough to quit and get married, have a child, divorce, and eventually write for a newspaper in the Bar Harbor area.

The second half of Real World follows Lorraine to an artist retreat in Virginia where she secures a residency and works on a book. The writing is her opportunity to investigate a double murder on the Appalachian Trail in Virginia, with the victims her former co-workers at Sunrise. Lorraine seems to want to explore the injustice that innocent, kind, good people are senselessly killed.

There are key plot points I am omitting. I do want to save for readers the opportunity for unexpected questions and reactions. You may not know what to make of the ending, and how to account for it. And this, perhaps, is the novel’s strongest recommendation—not what we know, but what we don’t.

Tina Cohen is a therapist who spends part of the year on Vinalhaven.