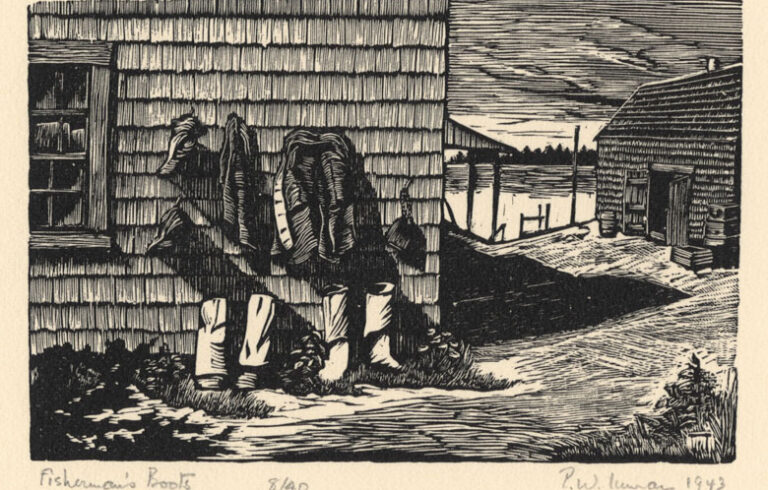

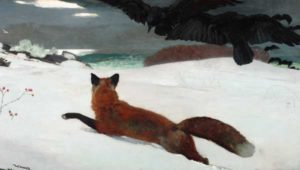

Images courtesy Portland Museum of Art

Winslow Homer settled at Prout’s Neck in Scarborough in 1883, 63 years after Maine became a state, and it was a momentous move: He would paint some of his most acclaimed canvases while in residence over the next 27 years. With the ocean practically breaking against his door, he produced remarkable seascapes that have lost none of their force and drama.

Homer gave us Maine winter. He broke the mold of the seasonal artist.

In the blockbuster show at the Portland Museum of Art, Homer is paired with sculptor Frederic Remington. The central premise is critical reappraisal: What roles did these artists play in shaping and perpetuating foundational myths about our nation and its peoples?

The PMA, Denver Art Museum, and Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth assembled top-notch critics and art historians to answer that sometimes thorny question. They also invited artists and others to weigh in on the work, an MO that inspired some criticism during the PMA’s N.C. Wyeth show last year.

For this Homer aficionado, the exhibition is a greatest hits delight, with major loans from around 35 museums and collections across the country. The show also provides an occasion to assess his legacy.

The exhibition highlights an aspect of that legacy at times overlooked in purely art-historical accounts: Homer gave us Maine winter. He broke the mold of the seasonal artist—a pattern that actually held, with a few major exceptions (Rockwell Kent, Andrew Winter, and Carl Sprinchorn come to mind), until the 1980s when more painters started living here full-time.

The PMA exhibition offers a bounty of Homer’s snow-and-ice paintings, including the iconic Fox Hunt and Coast in Winter, Watching the Breakers: A High Sea and Below Zero. The last-named features two figures in bulky winterwear making their way through snow toward the sea, their snowshoes for some reason in their hands, not on their feet.

Homer also broke ground in technique. With their loose under drawing, his watercolors proved liberating to future watercolor specialists like John Marin. At the same time, he accomplished feats of representation in this misbehaving medium that remain awe-inspiring. Look, for instance, at his paintings of fish. In Fish and Butterflies, a couple of monarchs share the air with a leaping yellow perch while An Unexpected Catch provides a close-up of a sunfish taking the fly of a fisherman casting from a nearby canoe. The delineation is superb.

The story of The West Wind, as recounted by Philip Beam in his ground-breaking Winslow Homer at Prout’s Neck (1966), offers an example of Homer’s unconventional approach to color—even if it was prompted by a dare. Fellow artist John La Farge had criticized Homer’s overuse of brown, so the latter bet him $100 that he could “paint a picture in browns which would be accepted and admired by critics and the public as well.” Homer ended up the victor and the painting took its place among his most popular.

Homer set the stage for future Maine painters, most notably perhaps, Robert Henri, the famed painter/teacher who created what might be called “The Monhegan School” through his promotion of the island to his students, among them, Kent, George Bellows and Edward Hopper.

In a 2012 essay on Homer’s Weatherbeaten from the PMA collection, art historian Thomas Denenberg cited Henri’s endorsement in his 1923 book The Art Spirit: “(Homer’s) work would hold a business man straight. He gives the integrity of the oncoming wave. The big strong thing can only be the result of big strong seeing.”

Henri’s language may seem hyperbolic by today’s art appreciation standards, but it’s one artist responding to another’s art with genuine reverence. Homer’s paintings continue to inspire such reactions: He saw strong.

“Mythmakers: The Art of Winslow Homer and Frederic Remington” runs through Nov. 29. A substantial hardback catalogue, Homer|Remington, is available through the museum.

Carl Little is author of Winslow Homer and the Sea and Winslow Homer: His Art, His Life, His Landscapes.