In the early 1970s, Jon Wilson realized he wasn’t as good a boatbuilder as others whose works he admired. But he was a pretty good thinker about boatbuilding.

“At that time, wooden boats had been going out of fashion and fiberglass boats were coming in, big time,” he recalled. “I just wanted to make sure that these things didn’t go extinct so fast that we lost the understanding of the art and science of wooden boat design and construction that deserved to be preserved.”

Today, many in the boating world know Wilson as a legend who in 1974 founded WoodenBoat magazine and its later spinoffs, Professional BoatBuilder magazine, Small Boats magazine, the WoodenBoat School, the WoodenBoat Store, and the WoodenBoat Show.

“I had two subscribers when I went to press. That’s the triumph of hope over experience.”

Those taking classes at the boatbuilding and traditional seamanship school are also familiar with the expansive campus—an idyllic spot of fields and woods overlooking the sea in the small coastal town of Brooklin—that has been the hub of the enterprise since 1981.

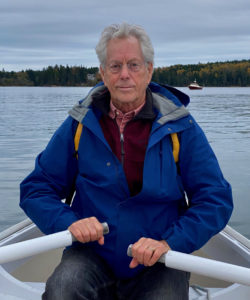

Now age 76, Wilson recently sold the business to two trusted employees who are as passionate about carrying forward the WoodenBoat legacy as its founder.

At the stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve, Wilson finalized the sale of the enterprise to Matt Murphy, the longtime editor of WoodenBoat magazine, and Andrew Breece, the publisher of the company’s magazine division. Wilson retained ownership of the 61-acre campus; the business will continue operations there on a lease.

“I had planned to die at my desk in my 90s,” said Wilson, an easygoing personality with the same boyish look he had in his 20s. “The pandemic made me realize that I cannot wait any longer. I could be gone next month. And there are other things I want to do, including record the history of WoodenBoat.”

‘LUCKY BREAKS’

Wilson learned to build boats at Dutch Wharf, a boatyard and marina in Branford, Conn., dating back to 1955.

“My life is a story of lucky breaks,” he said. “Without Dutch Wharf, there would be no WoodenBoat magazine. I would not have known enough or felt enough to start this enterprise.”

He credited the yard’s founder, Jack Jacques, with inspiring that passion.

“Dutch Wharf was a place you could take your wooden boat and have it refurbished, rebuilt, and repaired to the highest standards,” he said. “I hadn’t even known those standards existed when I got a job there in the mid-1960s. I took to it like a duck to water.”

He was fascinated by the science behind the craftsmanship. That take informed everything about his career going forward.

“I could begin to build an understanding of things that can go wrong if you don’t build and take care of the boats in a certain way,” he said.

At the time, wooden boats were still just “boats.” But fiberglass was gaining. Wilson saw that his mentors had knowledge and skills in a segment on the wane.

“I thought, ‘We cannot let this wisdom just go extinct,’” he recalled. “I wanted to preserve the wisdom of these boats and I believed there were others in the world who also wanted to see that wisdom preserved.”

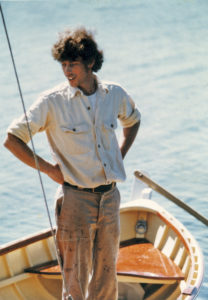

In 1970, Wilson moved to Maine to work as a boat carpenter at the Hurricane Island Outward Bound School. Soon, he moved to Pembroke, in eastern Maine, where he could afford a waterfront parcel to open his own shop. The problem?

“There was no clientele to speak of for the kind of boats I wanted to build, which was small, traditional, fine wooden boats,” he said.

That’s when he turned to the idea sparked at Dutch Wharf—documenting the intricacies of the wooden boat and yacht industry. He moved to Brooksville near Blue Hill, where there were more boats and people, built a small off-grid cabin, and began to implement his vision for a magazine that taps into the knowledge and experience of boatbuilders.

The Journal of the American Medical Association was the model for how professionals share information, especially about problems and solutions. As someone who loved magazines since he was a kid, he wanted high-quality paper, color photos, and elegant layouts.

“When I realized I was going to try to do this, I wrote to a few publication printers and basically said, ‘How do you print a magazine?’” he recalled. “I did not want it to be a newsprint rag.”

There’s an iconic photo of Wilson, talking on a phone housed in a watertight box fastened to a tree three-quarters of a mile from his cabin. He and a small team got the first issue out despite the inconvenience.

“It’s crazy, because I knew nothing,” he said. “But I’m thinking, ‘I’m going to give it a try.’”

Financed by the sale of his boat, the first print run was 13,000 issues.

“I had two subscribers when I went to press,” he said. “That’s the triumph of hope over experience.”

In September 1974, the team took a few cartons of magazines to the Newport (Rhode Island) Sailboat Show and sold 400 copies and 200 subscriptions.

The content was unique in the publishing world; that initial interest was encouraging. By the end of the first year, word of mouth and a bit of advertising drew almost 9,000 subscribers.

Over the next decade, readership grew to over 100,000. WoodenBoat became a bestseller on the newsstand and developed a loyal subscriber base, thanks to a synergy with wooden boat builders, owners, and fans.

In 1981, WoodenBoat relocated to a former 61-acre seaside estate in Brooklin.

“We had almost 50 people here during the heady days,” he said.

Over the years, publishers inquired into buying WoodenBoat. Wilson was committed to keeping the enterprise in Brooklin. Prospective buyers wouldn’t make that guarantee.

“I realized that I have a business that is employing a lot of people in the community and nothing mattered more than that,” he said.

The best thing, he realized, would be to put the enterprise into the hands of like-minded people, preferably from the inside.

“The more that percolated, the more it became obvious that Matt and Andrew were the ones,” he said. “Matt represents the traditional/content side and Andrew represents the future/marketing side. There was an elegance in that combination. I thought, ‘If these guys want to do this, then I want to make it easy for them.’”

And now? Wilson and his wife, Sherry Streeter—a graphic designer instrumental in implementing the WoodenBoat vision early on—have their home on the campus, so they’re around. Wilson is still in his office as founder and director of JUST Alternatives, a nonprofit committed to supporting victims/survivors of violence and violation and advancing victim-centered practices in justice and corrections.

Wilson often travels the country to provide victim offender dialogue facilitator training.

Today, WoodenBoat is a touchstone reaching far-flung readers who, in turn, reach back with their own stories.

“All I was trying to do was slow the process of extinction down—I’m fond of putting it that way,” he said. “I did not expect that what happened with WoodenBoat would happen. I thought, ‘I should do my best’ I thought, ‘I should give it all I could.’”